Thierry Mugler

Thierry Mugler has had a busy year at the FIDM Museum; his work was recently on display in Thierry Mugler: Alien to Angel on our Orange County campus, and two of his ravishing runway looks are on view in our newly-opened Los Angeles exhibition Capturing the Catwalk: Runway Photography from the Michel Arnaud Archive, open until July 7. With more of his designs on display in Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a massive retrospective planned at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, Mugler is definitely having a moment. (Note: all photographs from The Michel Arnaud Archive, Gift of Arnaud Associates)

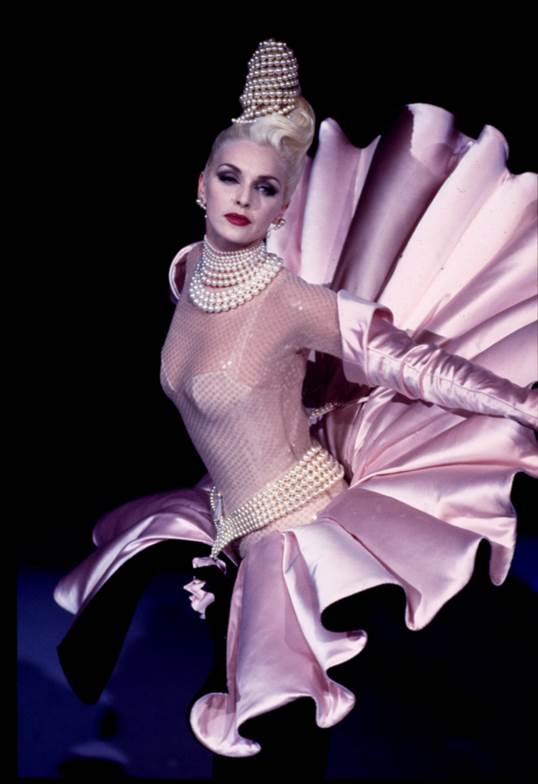

Thierry Mugler spent his childhood in Strausborg, the fairytale French city on the border between France and Germany, where he was born in 1948. In the shadows of the Strasbourg cathedral - which inspired his fascination with heaven, angels, and the Madonna figure - Mugler began to create worlds of his own fantasy. Comic books in particular connected with Mugler’s love of storytelling, and his childhood devotion to the medium is demonstrated clearly in his future runway shows.

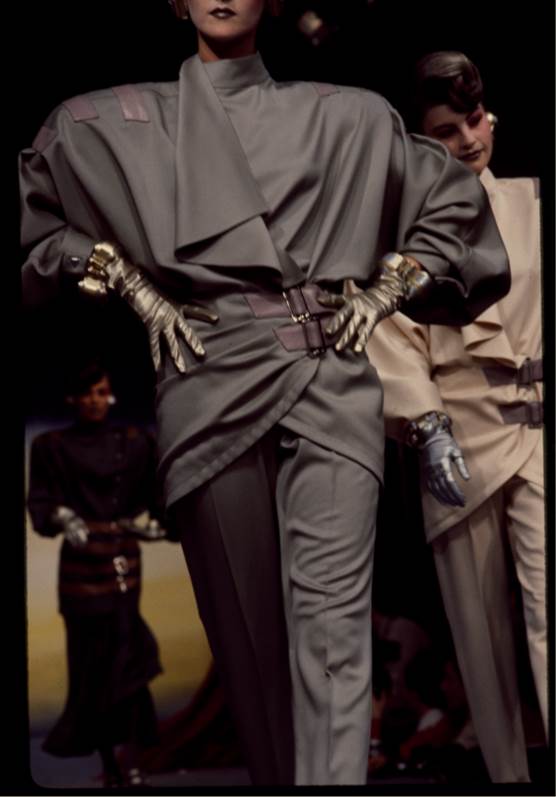

Though he never had any formal training as a designer, Mugler was educated for a short time at the decorative arts school of Strausborg. But the passion that truly dominated his youth was dance. He joined as a corps member of the Opera National du Rhin ballet company at just 14 years old, and danced professionally for 6 years. His time in the ballet would influence the anatomical look of his future collections. He explained, “Dance taught me a great deal about physical bearing, the organization of a piece of clothing, the importance of the shoulders, and the rhythm and interplay of legs.” Of course, his time on the stage also inspired his zeal for theatricality, the highlight of every Mugler runway show.

It was dance that eventually brought Mugler to Paris in the late 1960s as he tried to find a contract with a higher profile ballet company. In the meantime, he found a job as a window dresser at the fashionable Parisian boutique Gudele, where his colorful self-styled ensembles garnered much attention. He took this as a sign, and embarked on a new path as a freelance designer, selling his sketches to local fashion houses. In 1973, he launched his first women’s fashion collection under the name “Café de Paris.” The following year, he rebranded as “Thierry Mugler,” and the star was born.

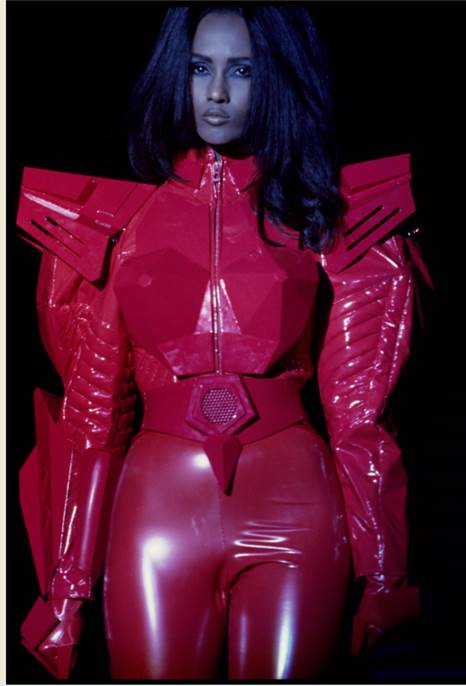

Mugler was one step ahead of the zeitgeist in predicting the angular silhouette that would dominate the 1980s. This decade was all about progress – particularly in the world of technology. These trends worked in harmony with Mugler’s interests – he frequently experimented with new materials in his designs, using PVC, vinyl, plastic, metal, plexiglass, and other unconventional resources to revolutionize high fashion. Mugler’s fascination with powerful females also synced perfectly with society’s growing acceptance of women in the workplace in the 1980s. Just as women needed the armor to fight their way up the ladder, there was Mugler with his army of broad-shouldered Amazons. He explained, “When you start to have shape, you feel stronger. My clothes exude power and sensuality and influence.”

Film in all forms also greatly inspired the designer, from Italian cinema to horror movies, but it was his love of classic Hollywood glamour that translated into the angular shoulders and hand-span waists he favored in almost every collection. When asked who his favorite designer was by Women’s Wear Daily, he named Travis Banton and his work for Marlene Deitrich; he called Hollywood “America’s haute couture.”

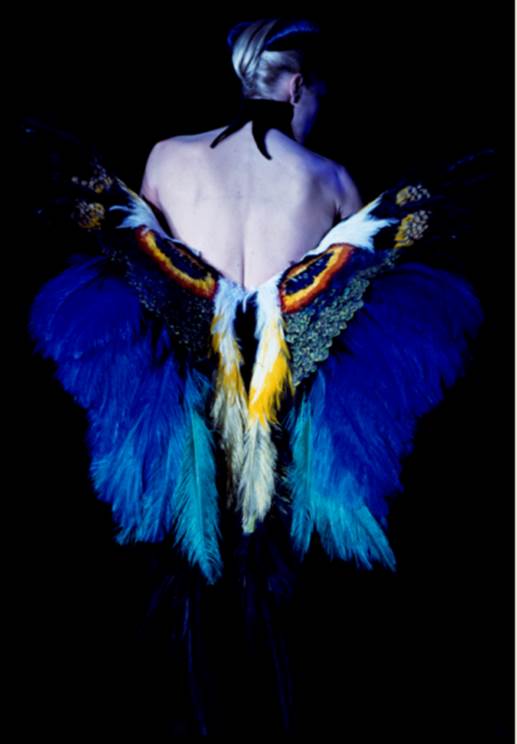

Perhaps Mugler’s greatest fashion legacy is his over-the-top fashion shows. Beyond the practical purpose of a fashion show, Mugler saw an opportunity to build new worlds of fantasy. He viewed it as a complete theatrical production: he made storyboards for every moment from start to finish and oversaw the hair, makeup, music, and models. With all of the cost, planning, and effort put into these presentations, it was no wonder the house didn’t put on a formalized show every season – it would have been impossible. For the off years, the collection was shown in a more traditional showroom.

Mugler saw that the fashion show could be about creating a desire for the brand – aspirational selling – and this realization was quite groundbreaking. He was inviting the consumer to be a part of his imagination; wearing one of the more conventional suits or dresses – or later, a Mugler fragrance – would still be a connection to this whimsical world. On occasion, Mugler physically invited customers into his world as well. His 1984 angel-themed fashion show was a celebration of the Mugler brand’s 10th anniversary. Half of the audience in the Zenith arena in Paris was made up of the normal press and buyer contingent, but the rest were members of the public that had bought tickets to the event – an unprecedented move for a fashion show. The 20th anniversary show was televised in France.

In 1992, Mugler was invited to present his first couture collection by the Chambre Syndicale de la Couture Parisienne. In typical Mugler fashion, he caused a stir by showing ready-to-wear pieces alongside his couture garments – he had long asserted that the craftsmanship of his ready-to-wear collections were just as precise as couture. 1992 was also the year that he partnered with Clarins to create his first perfume, Angel. Unlike other brands that license their name to manufactures, Mugler instead joined forces with Clarins so each had a stake in the business. He was involved in every aspect of developing the scent, combining notes of chocolate and coffee to create a pioneering gourmand fragrance. Angel was a blockbuster success, and remains a consistent international best seller – often climbing ahead of the iconic Chanel no. 5.

As Mugler’s perfume business grew exponentially throughout the late 1990s, his clothing line sales began to slow. Fashion on the whole seemed to be entering an identity crisis of sorts – bouncing from Versace’s high octane glamour to Marc Jacobs for Perry Ellis grunge. Mugler understood the pendulem spring and what he called the total rebellion against fashion, but for him, clothes were about joy. Neither the waif look nor minimalism synchronized with Mugler’s aesthetic; his attempts at unstructured, loose garments just looked out of place. In 2003, Clarins shut the fashion side of Mugler, concentrating only on fragrance and cosmetics.

Thierry Mugler was not one to retreat into an early retirement. He has spent the past two decades creating works of art for the stage, including Cirque du Soliel and two of his own burlesque cabarets. His most visible collaboration to date was his work with Beyoncé for her 2009 “I Am Sasha Fierce” tour. Beyoncé encountered the designer’s motorcycle bustier when it was highlighted in the Costume Institute exhibition Superhero’s: Fashion and Fantasy. It impressed her so much, she contacted Mugler design her costumes and come aboard as a Creative consultant for the tour. With thirty years-worth of work behind him, there are endless ideas and themes and cultural movements to discover in Mugler’s world – it is a treasure trove of fantasy. Mugler, a master of balancing extremes, believed there was room for both the creative and the commercial in fashion. He declared, “My fashions do have their place in the real world. When something touches you by giving you some happiness or a little bit of fun, it has its place in the world. I want my clothes to do that. Everyone has a right to create fun for themselves.”