Schiaparelli and Dalí

Telephone, shoe, lobster: unremarkable objects that Italian designer Elsa Schiaparelli and Spanish artist Salvador Dalí elevated to art and high fashion during their many years of fruitful collaboration. Though Schiaparelli was renowned for her partnership with several celebrated artists of the mid-twentieth century (Man Ray, Christian Bérard, Jean Cocteau, and Meret Oppenheim to name a few)[1], she and Dalí shared an unparalleled synergy that resulted in some of the most important creations of the Surrealist movement.

Dalí and Schiaparelli, circa 1949. Photo: Courtesy of Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí

Though their first encounter is not recorded, they likely met through mutual acquaintances in Paris’s flourishing art scene in the early 1930s. The years between the wars in Europe were an especially productive period for artists – reeling from horrific violence and increasingly aware of mounting political tensions – resulting in daring works that sought to shock audiences. Surrealism evolved from the Dadaist movement and explored the “isolating, modifying, and comprehending of ordinary objects and their meanings.”[2] Surrealists, who were particularly drawn to the human body, found in fashion a blank canvas for experimentation. Artists explored the “free play of the unconscious and the juxtaposition of unlikely elements”[3] though fashion design, fashion advertising, and window displays, where mundane mannequins were transformed into fascinating sculptures. However, it should be noted that not all Surrealists approved of this commercial association; some felt it violated the movement’s original principles.[4] It was in this culture of novelty, “wild imagination, and dreamlike visions”[5] that Schiaparelli and Dalí formed their artistic alliance. Indeed, Schiaparelli considered herself an artist before designer – she proclaimed dressmaking “not a profession but an art” in her 1954 autobiography Shocking Life. Both Schiaparelli and Dalí explored the female form and its interaction with clothing in their work, subverting “traditional notions of women’s roles and beauty, embracing and exaggerating the transgressive nature of fashion.”[6] Both were extremely precise in their crafts, whether brushwork or tailoring.[7] Perhaps most importantly, both felt strongly the need to produce fresh, audacious, and explosive designs, without boundaries or limitations.

Dial Compact Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dali, 1935 Gift of Joan Beer Damask and Donald Damask, 2015.1250.45

Dial Compact Elsa Schiaparelli and Salvador Dali, 1935 Gift of Joan Beer Damask and Donald Damask, 2015.1250.45

Schiaparelli and Dalí’s first collaboration from 1935 is currently on display in the Museum’s Acquiring Beauty: FIDM Museum Fashion Council, Est. 2011 exhibition: a small black lacquer compact made to look like the face of a rotary telephone. The piece is a harbinger of the duo’s work together over the next decade, as it encapsulates the basic tenants of Surrealism. It displaces a routine object, the telephone, thus causing a “contradiction between accustomed recognition and its new definition in art.”[8] The viewer’s understanding of the object is momentarily confused while the mind works to interpret its new role.[9] Yet however artful the object, fashion remains at its core a business; the ‘Dial’ compact appeared on the shopping pages of Harper’s Bazaar (referred to as one of “a handful of minor madnesses from Schiaparelli”[10]), and could be personalized with a woman’s initials. The design has spurred countless reproductions – either authentic, counterfeit, or ‘inspired by’ – over the past 80 years, proving the everlasting appeal and whimsy of an ordinary object transformed into art.

The lobster dress famously worn by Wallis Simpson and photographed by Cecil Beaton (a reference to Dalí’s fascination with the crustacean exoskeleton and sexual connotations of lobsters); the irreverent shoe hat; the bureau drawer suit; the skeleton dress; and the trompe l’oeil tear dress all followed the telephone compact in quick succession in the second half of the 1930s. The tear dress, part of Schiaparelli’s 1938 Le Cirque collection, was a particularly bold design; it channeled the aggressive overtures of war in Europe, went against the “customary decorum”[11] of eveningwear, and predated the punk movement’s vogue for ripped clothing in the 1970s. Schiaparelli returned to fashion after the perils of the war years, but never recaptured the creative frenzy of this prolific period. In Shocking Life, Schiaparelli reflected on this seminal moment in her career: “Working with artists like Bebe Bérard, Jean Cocteau, Salvador Dalí, Vertès, Van Dongen; and with photographers like Hoeningen-Huene, Horst, Cecil Beaton, and Man Ray gave one a sense of exhilaration.”[12] For his part, Dalí fervently expressed the depths of their combined artistic brilliance in his 1942 book The Secret Life of Salvador Dali. He refers to Schiaparelli's 1935 move to the Place Vendôme in Paris: “Here new morphological phenomena occurred; here the essence of things was to become; transubstantiated; here the tongues of fire of the Holy Ghost of Dalí were going to descend.”[13]

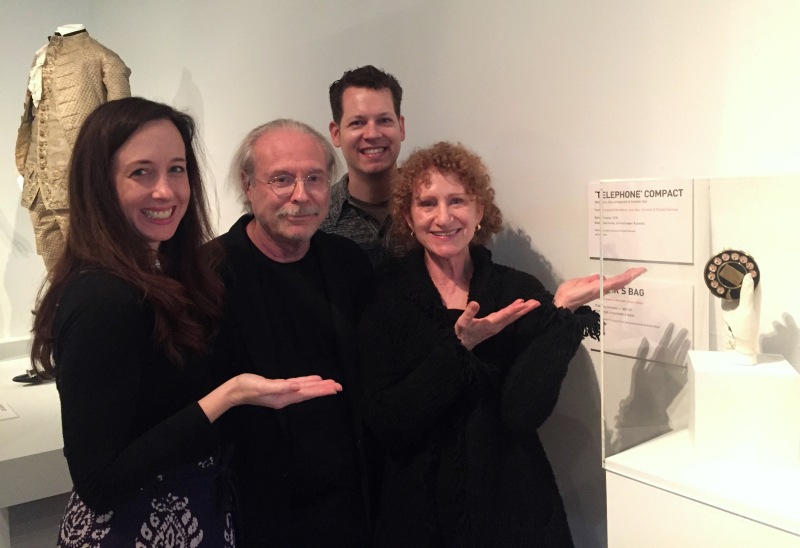

Associate Curator Christina Johnson and Curator Kevin Jones with Fashion Council members Donald Damask and Joan Beer Damask, donors of Schiaparelli & Dalí Dial Compact from 1935.

Associate Curator Christina Johnson and Curator Kevin Jones with Fashion Council members Donald Damask and Joan Beer Damask, donors of Schiaparelli & Dalí Dial Compact from 1935.

[1] Abigail Cain, “Fashion Designer Elsa Schiaparelli Made Dalí’s Art Wearable,” Artsy.net, December 7, 2017, https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-fashion-designer-made-dalis-art-wearable [2] Richard Martin, Fashion and Surrealism (New York: Rizzoli, 1987), 15. [3] Dawn Ades, Schiaparelli and the Artists (New York: Rizzoli, 2017), 48. [4] “Surrealism and Design,” Victoria & Albert Museum, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/s/surrealism-and-design/ [5] In Daring Fashion: Dalí & Schiaparelli, The Dalí Museum, Past Exhibits, http://thedali.org/exhibit/dali-and-schiaparelli/ [6] Ibid. [7] Steff Yotka, “Dalí and Schiaparelli Invented the Art-Fashion Collaboration – A New Exhibit Celebrates Their Shocking Works,” Vogue.com, October 12, 2017, https://www.vogue.com/article/dali-schiaparlli-in-daring-fashion-exhibit-dali-museum [8] Martin, Fashion and Surrealism, 107. [9] Ibid. [10] Harper’s Bazaar, October 1935, 175. [11] Martin, Fashion and Surrealism, 136. [12] Schiaparelli website – a shocking life [13] Salvador Dalí, Translated by Haakon M. Chevalier, The Secret Life of Salvador Dalí (New York: Dover Publications, 1942, reprinted 1993), 394.