Royal Relic: Documentation and Ongoing Research (Part Two)

We're back with Part Two of Curator Kevin Jones' series on an exciting new acquisition: an exquisite evening ensemble belonging to Queen Alexandra. In this post, Kevin tracks existing documentation of Queen Alexandra's wardrobe and connects it to this newly discovered object. Plus, he turns to royal wardrobe scholar and renowned fashion historian Dr. Kate Strasdin for her expert opinion. Want to learn more about Kate and Kevin's collaboration on this project? Watch our Instagram Live on Friday, May 15 at 11 am PST for the first FIDM Museum Collection Conversation, a Q&A between Kate and Kevin! They will discuss the significance of the ensemble, what it means for Dr. Strasdin's ongoing research, and answer questions from viewers. If you have a question you'd like to submit, we invite you to leave a comment on this post. ************************************************************************************************************************************************************************* The FIDM Museum’s latest acquisition is a beautifully embroidered evening ensemble made for Queen Alexandra of England at the time she was newly crowned. The three-piece outfit is synergistic with a wool blouse, also in our collection, that she wore as the new Princess of Wales forty years before. After waiting decades to ascend the throne, Edward VII finally became king on January 22, 1901, on the death of his long-reigned mother, Queen Victoria (1819-1901). The first year of mourning allowed time to prepare for the coronation (and Edward’s recovery from an emergency appendicitis), which finally took place in Westminster Abby on August 9, 1902.

![299404-1341394250[1]](/sites/default/files/featured_images/img_602f4006682c8.jpg)

King Edward VII and Queen Alexandra in coronation robes, 9 August 1902. Photographer: W & D Downey (active 1855-1941). Royal Collection Trust, RCIN2933174.

By this time, Alexandra had left off deep mourning and wearing dull black crepe. For the coronation year, she dazzled in spangled court dresses that showed off her celebrated figure and status as the highest titled woman in the United Kingdom and its dominions. By this stage in her life (nearing 60 years), Alexandra’s daywear was British made, but her evening attire was mostly French. She mainly patronized three couturiers in Paris: Morin-Blossier, Laferrière, and Favre.

Designer’s label in Reception Bodice, Henriette Favre, Paris, ca. 1902-06. FIDM Museum Purchase: Funds donated by Barbara Bundy, 2020.5.21A/C.

Designer’s label in Reception Bodice, Henriette Favre, Paris, ca. 1902-06. FIDM Museum Purchase: Funds donated by Barbara Bundy, 2020.5.21A/C.

This ensemble was created by the latter, and is typical of the house style when compared to other examples worn by Alexandra. Henriette Favre (dates unknown; worked at least from the 1890s to the 1910s) specialized in allover embroidered patterns, especially favoring flat metal sequins that gave maximum glitter under incandescent lights.

Sleeve detail, Reception Bodice, Henriette Favre, Paris, ca. 1902-06. FIDM Museum Purchase: Funds donated by Barbara Bundy, 2020.5.21A/C.

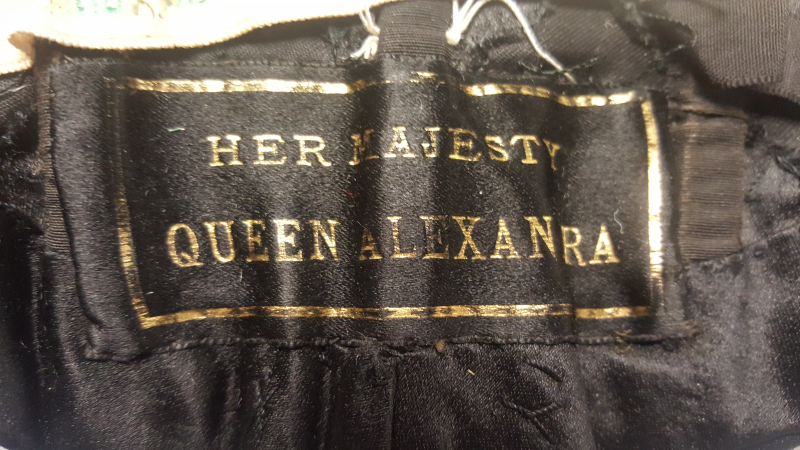

During an email correspondence with Dr. Kate Strasdin, biographer of Alexandra’s wardrobe, she enumerated from Her Majesty’s accounts—held in the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle—the specific amounts spent for Favre garments alone: February 1898 – £370.12.7 for 1897 [F.27, voucher No. 80] October 1898 – £293.17.4 for May 1897 [F.28, voucher No. 258] February 1899 – £165.13.5 for Dec 1898 [F.30, voucher No. 107] April 1900 – £219.18.1 for year 1899 [F.33, voucher No. 158] December 1903 – £548.14.7 for December 1903 [F.41, voucher No. 386] February 1905 – £466.15.6 paid to February 1905 [F.29, voucher No. 147] November 1905 – £486.10.3 paid to November [F.30, voucher No. 308] February 1907 – £790.10.2 from December 1906 [F.34, voucher No. 147] December 1907 – £432.5 from September 1907 [F.38, voucher No. 510] August 1908 – £303.14.11 from June [F.42, voucher No. 7] July 1909 – £779.16.10 from June [F.46, voucher No. 8] [RA.VIC.ADD A21 219 B] Every January, April, July, and October, the queen received a quarterly Privy Purse allocation of £2500 that covered clothing purchases, but also their care and maintenance and the salaries of her ladies-in-waiting. In December 1902, there was a separate Favre invoice for £891.16 not included in the main wardrobe accounts. It was listed under “French Bills of 1902” and was probably a one-time payment, as part of the Coronation expenses that fell outside her normal allowance. Sadly, no information was recorded about the actual garments, only these sums of money paid. How do we know Queen Alexandra owned this particular ensemble? There are specialized nametags sewn into the ball bodice and skirt waistbands.

Queen Alexandra’s personal label in Ball Bodice, Henriette Favre, Paris, ca. 1902-06. FIDM Museum Purchase: Funds donated by Barbara Bundy, 2020.5.21B/C.

Queen Alexandra’s personal label in Ball Bodice, Henriette Favre, Paris, ca. 1902-06. FIDM Museum Purchase: Funds donated by Barbara Bundy, 2020.5.21B/C.

This gold stamped, black silk satin label is unique to Alexandra and is the principle means of identifying her clothing starting from 1901 that would otherwise be unknown without additional provenance; she did not use a similar label when Princess of Wales. Of course, any documentation about her queenly wardrobe is desirable to help place when and where she wore such garments before Edward’s death in 1910 and her official sartorial needs quickly curtailed (along with her government stipend). However, due to anonymity in the auction world, only rarely do consignors provide historical background about the objects they sell, resulting in a loss of continuity of knowledge. Happily, I was able to privately converse with the couple who sold this ensemble to the FIDM Museum via the Australian auction. They acquired the outfit in 2005 or 2006 at Tennants Auctioneers in Leyburn, North Yorkshire, England, and were told that it had descended in a family, the name of which was not released. Initially, I thought it might have come from a 1937 auction of Alexandra state gowns and accessories that sold in New York City—the majority of which ended up at The Metropolitan Museum of Art—though none of the lot descriptions pinpoints this particular design. Unaccountably, in 1951, the present ensemble appeared among a collection of eight of Alexandra’s gowns that were available for purchase at a London antique shop called Baroque. Where this group came from is unknown, but, amazingly, British Pathé filmed four of the gowns on models, as a cinema news feature titled Look Back For Inspiration. Three garments from the Baroque shop have been located. The Fashion Museum in Bath, England, acquired an evening gown through museum founder and dress historian Doris Langley Moore (1902-1989), who was given a choice of two gowns. She opted for an embroidered purple chiffon creation by the Paris couture house Doeuillet, which did not appear in the newsreel.

Evening Gown, George Doeuillet, Paris, ca. 1908-10. The Fashion Museum, Bath, England.

Evening Gown, George Doeuillet, Paris, ca. 1908-10. The Fashion Museum, Bath, England.

Incidentally, in the 1930s, Baroque also sold an early 1870s silk-plaid dress of Alexandra's that later entered the Bath collection. Another gown—and the first shown in the Pathé film—is now housed at the Bunka Gakuen Costume Museum in Tokyo, Japan, and is covered in gold metallic sequins imitating fish scales.

Evening Gown, ca. 1908. Bunka Gakuen Costume Museum, 03850.

Excitingly, the FIDM Museum evening gown is from the Baroque collection, as well, and is documented as the finale of the Pathé footage: seen from behind, the elegant model parades into view, turns, and sits on a chair. At the time, 1951, the gown looked to be in pristine condition. However, before the ensemble can be safely mounted on a mannequin today, its sparkling lace and netting will need the care of a textile conservator. We hope to exhibit both bodices and the skirt in 2025 for Queen Alexandra’s 100th anniversary year.

Queen Alexandra Ensemble - Ball Bodice from FIDM Museum on Vimeo.

Queen Alexandra Ensemble - Reception Bodice from FIDM Museum on Vimeo.

Queen Alexandra Ensemble - Skirt from FIDM Museum on Vimeo. I wish to thank colleague and friend Dr. Kate Strasdin for her help compiling this blog, answering many questions, and searching through her vast files to locate unpublished material about Alexandra’s purchases from Henriette Favre (all while sheltered-at-home with a husband and two sons requiring her attention!). Additional facts were gleaned from her terrific publication, which I highly recommend. But questions remain: Where did the eight Baroque garments originally come from, and do the business records of Maison Favre survive that might note this very ensemble? The research continues…