Remembering Kenzo Takada

In 1970, a small boutique in Galerie Vivienne, Paris - painted top to bottom with lush vegetation as a tribute to Henri Rousseau’s The Dream - brought a fresh sartorial perspective to the venerated fashion capital. The store, Jungle Jap, was an antithesis to the buttoned-up couture creations on Avenue Montaigne; instead, cheerful prints, bright colors, and voluminous silhouettes were executed in inexpensive cottons purchased at flea markets or the Marché Saint-Pierre, Montmartre’s discount fabric market. This clothing was dynamic and accessible, and the boutique attracted a young crowd eager to sway the tides of fashion’s status quo. The quiet man behind these free-spirited designs was Kenzo Takada (1939 - 2020).

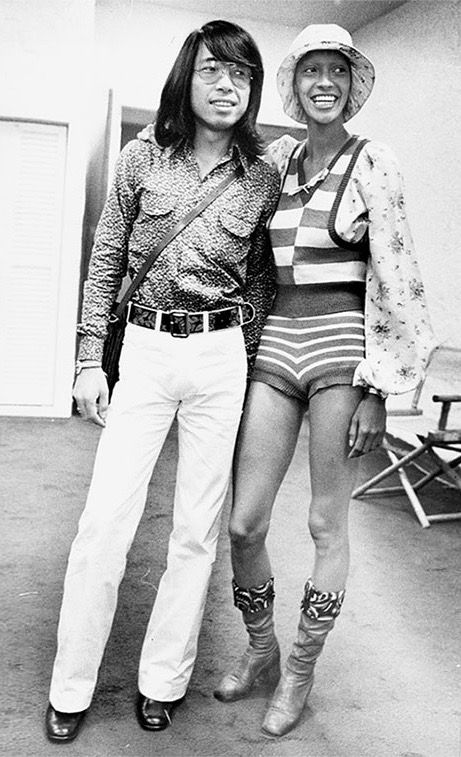

Kenzo Takada with Carol LaBrie, in his design, 1971. Photo: Richard Gummere / New York Post Archives / © NYP Holdings, Inc. via Getty Images

Growing up in Himeji, Japan, Takada was constantly drawing; in his career, he produced over 7,800 sketches.[1] Though he had always wanted to study fashion, there were few opportunities for men to enter the field in his home country, so he studied literature at Kobe University instead. When Bunka Fashion College in Tokyo began accepting male students, Takada was among the first to enroll. In 1960, he won a prize from Soen, a Japanese fashion magazine, and went on to design for the Sanai department store.[2] Yet it was the 1964 Tokyo Olympics that truly changed the course of his career. Takada’s apartment building was demolished to make way for the Olympic grounds, and he used the compensation money to fulfill his lifelong dream of visiting Paris. Along with a classmate from Bunka, Takada made his way to Paris via a month-long boat trip with stops in Hong Kong, Saigon (Ho Chi Minh City), Singapore, Colombo, Bombay (Mumbai), Djibouti and Alexandria.[3] This exposure to new countries, cultures, and people would have a profound impact on Takada’s design aesthetic. He frequently incorporated a “cultural kaleidoscope”[4] into his work, exploring folklore traditions and including a roster of diverse models in his runway shows. The trip inspired the motto for his future clothing line: the world is beautiful.

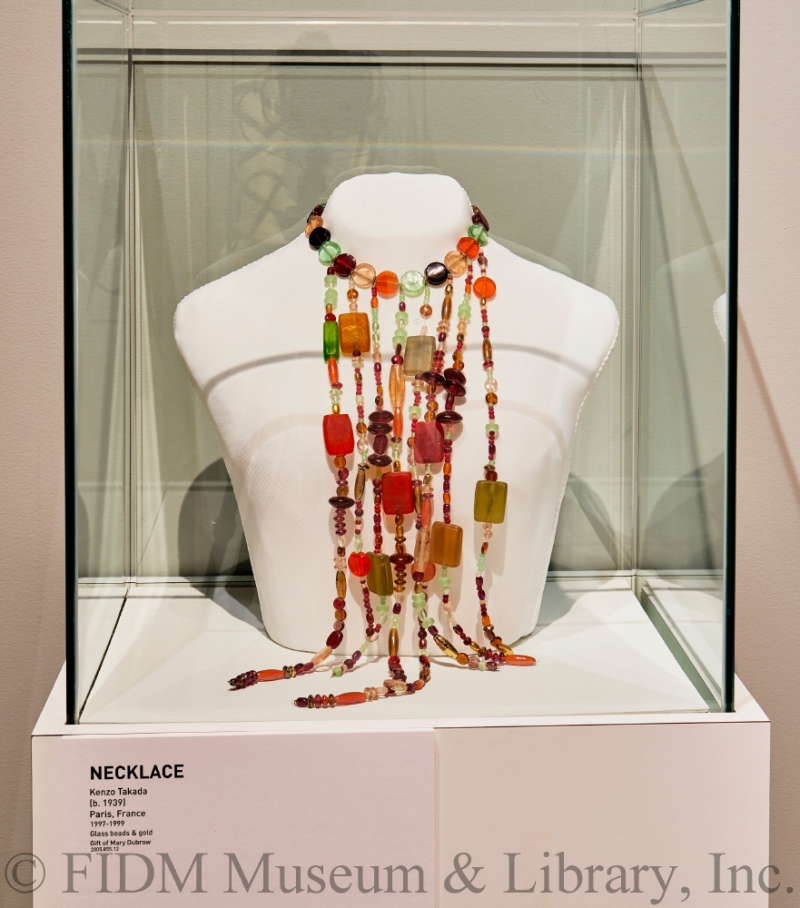

Glass beaded choker Kenzo Takada, 1997-1999 Gift of Mary Dubrow 2005.855.12

Glass beaded choker Kenzo Takada, 1997-1999 Gift of Mary Dubrow 2005.855.12

Takada fell under the spell of Paris. Though he intended to stay for a few months, he remained there for the rest of his life - over 56 years. He enrolled in language classes and made a meager living selling sketches to design houses, including Louis Féraud. He was hired at Pisanti, a clothing manufacturing company, where he produced drawings and garment toiles. In a 1965 letter to his mother, Takada expressed his joy and astonishment that he played an active role in the city’s fashion industry: “After all, being admitted into that world is what makes me happiest. Here, in Paris.”[5] Just five years after his arrival in Paris, Takada and two friends opened a boutique in the spirit of London’s progressive shops on King’s Road and Carnaby Street. The name - Jungle Jap - posed problems when the brand eventually expanded to New York and was sued by the Japanese American Citizens League. However, Takada defended his use of ‘Jap’, a derogatory term in the States, explaining “I thought if I did something good, I would change the meaning.”[6] The name was not an issue in France, and the store struck a chord with Parisians hungry for the freedom of movement and gaiety of Takada’s clothing. Takada had taken a trip home before designing his first collection, where he rediscovered the beautiful textiles and garments of Japan. The resulting fashions fused traditional Japanese styles with French sensibilities. Intentionally free of zippers, voluminous in silhouette, and constructed in lightweight fabrics, Takada’s clothing was “an expression of his complete personality.”[7] Jungle Jap displaced antiquated ideas of clothing and class; in Takada’s view, “Fashion is not for the few - it is for all the people. It should not be too serious.”[8] Shy and quiet, yet fun-loving and mischievous, Takada embraced the energy of the Paris club scene, dancing all night and designing all day (he jokingly admitted, "I didn’t sleep much between 1970 and 1971.”)[9] His runway shows, known for their spectacle and party-like atmosphere, became the hottest ticket in town. His global aesthetic influenced other designers, both on the couture runway and in ready-to-wear stores. He became known for mixing patterns and colorful floral fabrics inspired by his favorite painters. Takada stayed away from the business aspects of Jungle Jap in the early days, leaving the management to his partners, something that perhaps helped his initial successes. He recalled, “I did any old thing I felt like doing without analyzing whether it was commercial. I just happened at the right time - at the time when the young French woman was finally ready to let herself go.”[10]

Ensemble Kenzo Takada, S/S 1975 92.26.2AB

Photograph by Michel Arnaud Kenzo Takada, S/S 1975 Gift of Arnaud Associates

Photograph by Michel Arnaud Kenzo Takada, S/S 1975 Gift of Arnaud Associates

The FIDM Museum holds a S/S 1975 two-piece ensemble that exemplifies Takada’s design ethos: vibrant colors, cotton fabric, full skirt, and a loose wrap top with a tie closure. On the runway, the striped and madras top was paired with a floral skirt - combining patterns is also a Kenzo classic. He often utilized separates, as it allowed for more variety in mixing and matching pieces. Though he initially used cotton in his designs because it was all he could afford, Takada also appreciated the “lightness, comfort, and relaxed feel of cotton.”[11] Another ensemble in the Study Collection, a black acrylic/mohair knitted sweater and skirt, shows Takada’s skill with knits - a staple in his early collections. He honed his knitting techniques while working at Relations Textiles during his early Paris days. Though he was renowned for his dexterity with color, Takada did feature black and white designs as an homage to the theatricality and stark contrasts of Kabuki costumes.[12]

Ensemble Kenzo Takada, c. 1978 Gift of Bonnie Smith S2003.43.2AB

Ensemble Kenzo Takada, c. 1978 Gift of Bonnie Smith S2003.43.2AB

Jungle Jap continued to expand over the next decade, eventually changing the name to Kenzo and introducing lines of menswear, jeans, childrenswear, and fragrance in the 1980s. After selling his brand to the famed LVMH fashion conglomerate in 1993, he retired in 1999 with a spectacular retrospective fashion show. Never one to rest creatively, Takada took on several projects in the past two decades, including designing opera costumes, a housewares collection, a book exploring the Kenzo archives, and the launch of a new luxury lifestyle brand, K-3. His career came full circle when he designed the Japanese uniforms for the 2004 Athens Olympic games - the same event that allowed him to travel to Paris forty years earlier. Takada passed away on October 4, 2020 due to complications with Covid-19. That he died during Paris fashion week was not lost on the fashion community, many of whom pointed out his lasting influence on their craft. In a Vogue interview marking his retirement from Kenzo, Takada reflected, “My work was always about freedom and harmony. I’d like to be remembered as a designer who crossed boundaries.”[13]

[1] Kazuko Masui, Kenzo Takada (Paris: Hachette Livre, 2018), 41. [2] Vanessa Friedman, "Kenzo Takada, Who Brought Japanese FAshion to the World, Dies at 81," The New York Times, October 4, 2020. [3] Masui, Kenzo Takada, 319. [4] Armand Limnander, "Sayonara, Mes Amis," Vogue, April 1, 2000, 246, 250. [5] Masui, Kenzo Takada, 382. [6] Bernadine Morris, "Designer Does What He Likes - And It's Liked," The New York Times, July 12, 1972. [7] Juliet Buck, "Jap Happy," Harpers & Queen, February 1972, 49-51. [8] Morris, The New York Times. [9] Masui, Kenzo Takada, 38. [10] "Kenzo: The Big Influence," Women's Wear Daily, April 3, 1972, 56. [11] Masui, Kenzo Takada, 38. [12] Fleur Burlet, "Kenzo Takada 'Can't Do' Social Media," Women's Wear Daily, November 21, 2018, 14. [13] Limnander, "Sayonara," Vogue, 246, 250.