Ready-To-Wear, Italian Style

Emily Mushaben

In this blog post, we’re treated to a slice of Italian fashion by Emily Mushaben. Emily is a master’s candidate in her final year in New York University’s MA Costume Studies program and is the FIDM Museum’s Donald and Joan Damask 2021 Summer Study Grant Digital Intern. Before joining the NYU Costume Studies program she graduated from Arizona State University with a BA in Design Studies and a minor in Fashion. While an undergraduate, Emily completed a curatorial internship at the Phoenix Art Museum, and most recently, she was a curatorial intern with the Costume Institute at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Emily has a keen interest in post-modern fashion and art, and the intersection of architecture and fashion. Though Emily’s experience at the FIDM Museum was entirely virtual, she flourished. In her own words:

"My experience as a Digital Intern with the FIDM Museum this summer was incredible and taught me to translate my research skills to a digital platform. Although I worked remotely from my home in Brooklyn, New York, I continuously felt supported by the team and was able to explore the museum's extensive collection of digitized objects and photography. Thank you again for this valuable opportunity!"

Thank you, Emily, for your contributions. Read on for insights into the Italian fashion industry...

Did you know that the word milliner- in English meaning a person who makes hats- originally was used to describe a native or inhabitant of Milan, Italy in the 15th century? By 1783, and through the 19th century, the word referenced, "a woman who makes and sells bonnets and other headgear for women". Etymology, “milliner." The northern city of Italy has always been a center of production for men’s and women’s fashion and accessories, but Milan was not unanimously chosen over night as the fashion capital of the Mediterranean country. Instead, it was a progressive series of events and decisions that collectively over several decades pushed the industry forward towards global modernization.

Dating back to the 12th century, Italy has a long history of involvement in the fashion and textile industry. Luxury textiles like lavish cut velvets were handcrafted and produced in the city of Venice, leather shoes in Florence, and jewelry in Rome. Da Cruz, “Made in Italy.” These luxury fashion goods and accessories were bought and sold in local markets as well as exported for international trade, establishing a strong reputation for high-quality items made in the bel paese (“beautiful country” in Italian). Despite solidifying a reputation for international style and artisanal products, Italy lacked a unified fashion capitol because the country suffered from an unstable economy as a result of an insecure government. When the fascist regime, led by Benito Mussolini, was defeated at the end of World War II, Italy was left in a state of rebirth encouraging the fashion and textile industries to make strategic decisions towards unification.

Throughout the 1950s and 60s the Italian fashion industry was split between the cities of Rome, Florence, and Milan while a few fashion houses even left the country to move their business to Paris. Cole, “Modern Fashion,” 289. This phenomenon was coined “the parade from the Tiber to the Seine,” by the New York Times. Alden, “Welcoming,” 12. In an attempt to bring the press and the attention of the fashionable world back to Italy, businessman Giovan Battista Giorgini held the first successful high fashion show at his home in Florence on February 12th, 1951. The show exhibited designs by Emilio Schuberth, Sorelle Fontana, Contessa Simonetta Visconti, Roberto Capucci, Alberto Fabiani, Jole Veneziani, and Emilio Pucci. Present at this spectacle were press representatives from American department stores Bergdorf Goodman, Saks Fifth Avenue, and I. Magnin who then brought designs back to sell to their American clientel. Da Cruz, “Made in Italy.” Although this event was held in Florence, the modern sportswear silhouettes and styles were successful in drawing the attention of American clientel towards Italy instead of just Pzaris, which contributed to the future success of Milan.

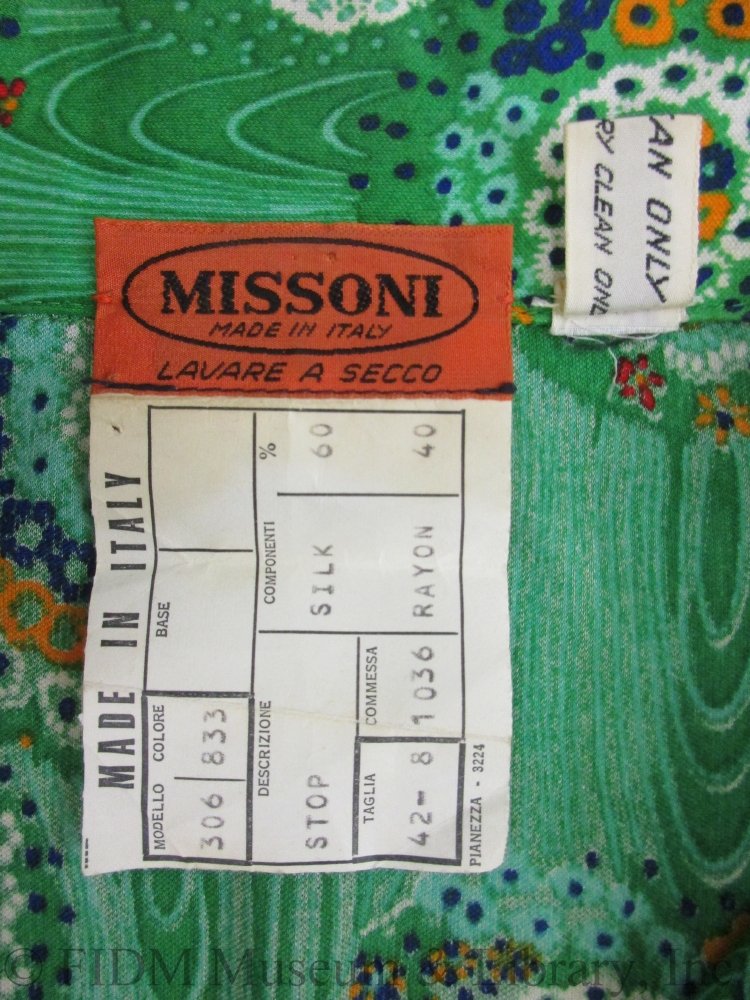

In the late 1960s and 1970s Italian design houses were particularly renowned for their high fashion apparel, leather accessories, and knitwear. Missoni, an innovative luxury knitwear company, first showed their ready-to-wear collection in Milan in 1966. “Missoni History.” After the success of their first presentation the company was invited the following year to show at the prestigious Palazzo Pritti in Florence. The Missonis sent their models down the catwalk wearing sheer Lurex dresses with no undergarments because Rosita and Ottavio didn’t like the way white bras looked under the dresses. “It simply wasn’t appropriate,” said Rosita, “they could keep the panties, but they had to take off their bras.” Missoni, “Family.” When the spotlights lit up the show the audience could see the models’ bare breasts, creating quite the scandal. Despite the success of their collection, Missoni was not invited back to show in Florence and returned to Milan. Shortly after their transition back to Milan the Missonis were introduced to Diana Vreeland who fell in love with the beautiful colors and patterns of their signature knit fabrics. “Who says a rainbow has seven colors? It has many shades,” Vreeland exclaimed after seeing the latest Missoni collection. Vreeland facilitated a business partnership between the Bloomingdales and the Missoni brand allowing for a Missoni ready-to-wear boutique to open in Bloomingdales in 1968 bringing Milan to New York City.

Day Dress

Day Dress

Missoni

c. 1974

Silk and rayon single knit

Gift of Mrs. Gerald Labiner

80.1974.008.15AB

Another ready-to-wear designer based in Milan was Laura Biagiotti; a second-generation Italian seamstress who honed her craft while working at her mother’s atelier. In 1990, Biagiotti was interviewed by Dr. Valerie Steele for her book Women of Fashion: Twentieth Century Designers where Biagiotti shared that she frequently joined her mother on trips to Paris and grew up observing the refined glamour of French couture. When she was older, Biagiotti took a trip to New York City to get a sense of American style and their taste in fashion. These two cities and their distinct styles of dressing had a lasting impact on Biagiotti and strongly influenced her design style. This American connection was typical of many Italian post-war designers, which had a great influence on the development of contemporary ready-to-wear and sportswear in Italy. Steele, “Angels,” 173. Biagiotti started her namesake ready-to-wear line in 1972 with the motto that a woman designer, “knows what kind of clothes a working woman needs,” she said.

Evening Dress

Laura Biagiotti

c. 1975

Polyester jersey and ribbed knit

Gift of Mrs. Robert Stack

84.1975.058.

Prêt-à-porter, or ready-to-wear, was in full swing during the 1980s in Milan. A March 1981 New York Times article said that the American buyers “placed orders in Milan for styles that very well might change the way women dress and think about clothes.” The article also notes that the designers, “have used a modern approach, emphasizing comfort, ease and freedom.” Morris, “Italian Fashion,” B16. By creating clothes for the contemporary woman the designers in Milan were acknowledging that the average consumer no longer wanted to go through the extensive process of visiting a dressmaker every time they wanted a new model, and instead would rather go shopping for ready made garments at their leisure. This new attitude towards dressing presented fashion as an individual expression.

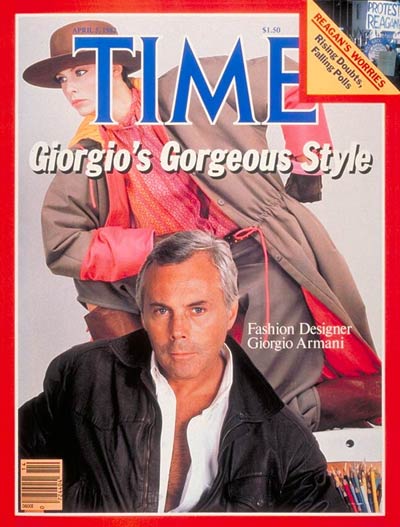

TIME magazine cover, April 5, 1982.

“Giorgio Armani: Suiting Up For Easy Street”

Cover credit: Bob Kreiger

A Milan based designer that deeply influenced modern ready-to-wear on a global scale in the 1980s was Giorgio Armani. Armani’s iconic designs were so popular that TIME featured the designer on the cover of their magazine in April 1982 saying, “Giorgio Armani defines the new shape of style.” When he was younger, Armani worked in the Italian textile industry at mills and factories learning about the qualities of good fabric throughout the 1960s. Along with this intimate understanding of fabric, Armani also studied tailoring and architecture; this provided him with a strong foundation when starting his own clothing line that was formed around his reinvention of the suit jacket. In the 1990 documentary short “Made in Milan,” directed by Martin Scorcese, Armani says that his reinvention of the structured suit jacket to a more fluid, casual, and romantic design was the point of departure for everything he created, and that his crucial discovery was making jackets that fell in an unexpected and natural way. His jackets were “like a second skin,” Armani said, that allowed both men and women to move freely and comfortably.

Man’s Jacket

Man’s Jacket

Giorgio Armani

C. 1980s

Wool and camel hair

Gift of Max Ember

2014.1327.3

By the 1990s Milan was internationally recognized as Italy’s capital of fashion and was a routine stop for journalists and editors alike during their twice annual ready-to-wear fashion month tour. Milanese alta moda design houses like Versace and Prada punctuated the last decade of the twentieth century and set the standard for the next generation. The influence of Italian fashion is undeniable and the history of Milan as the epicenter of this influence is truly remarkable!

Sources:

Alden, Robert. “French Are Welcoming New Italian Designers.” The New York Times, December 10, 1962.

Cocks, Jay. “Giorgio Armani: Suiting Up For Easy Street.” TIME, April 5, 1982. Accessed July 7, 2021. http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,921182,00.html.

da Cruz, Elyssa. “Made in Italy: Italian Fashion from 1950 to Now.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. (October 2004). http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/itfa/hd_itfa.htm.

Steele, Valerie. “Chapter 14: Angels Have No Sex.” In Women of Fashion: Twentieth Century Designers. New York: Rizzoli International, 1991.

Cole, Daniel and Nancy Deihl. The History of Modern Fashion: From 1850. London: Laurence King Publishing, 2015.

Scorcese, Martin. Made in Milan. 1990. https://www.indiewire.com/2013/10/watch-martin-scorseses-rare-1990-giorgio-armani-documentary-made-in-milan-248903/.

“Milliner,” Online Eytomology Dictionary, accessed July 7, 2021, https://www.etymonline.com/word/milliner.

Missoni. “A Family Always In Fashion.” Missoni World. Accessed July 9, 2021. https://www.missoni.com/world/editorial/brand/history/.

“Missoni History Revisited,” Pilaeo, August 11, 2015. https://magazine.pilaeo.com/missoni-history/.

Morris, Bernadine. “Italian Fashion’s Success: A Fresh Point of View.” New York Times, March 31, 1981. https://www.nytimes.com/1981/03/31/style/italian-fashion-s-success-a-fresh-point-of-view.html.