Model Behavior: Black Beauty & Sartorial Ingenuity Through The Lens Of The Ebony Fashion Fair – Part Two

In Part II of Model Behavior: Black Beauty & Sartorial Ingenuity Through the Lens of the Ebony Fashion Fair, Iesha Coppin-Forde continues her examination of black beauty products, models, and the fashions they modeled for Ebony’s sensational Fashion Fair. Iesha was the museum’s Lori and Sal Santamaura 2021 Summer Study Grant Digital Intern; a very special issue of Ebony in our collection caught Iesha’s eye and sparked her research. Read on to find out how this Ebony relates to fashions we have in our collection!

PART II

Eunice Johnson (1916 – 2010) skillfully asserted Black culture into an international market that catered to a white majority. Her discerning eye acquired garments from Yves Saint Laurent to Valentino, while the purchasing of designer garments didn’t always come easy. Approaching the European market was met with discrimination and resistance; as some designers argued, they feared “losing clients if their clothes appeared on black models,” Aubry, Alex. "Chronicles of chic: Mrs. Eunice Johnson," System Magazine, System issue No.1, 160. says, Alex Aubry. Mrs. Johnson utilized the power of cash to acquire the best for Ebony Magazine, mentioning an essential phrase before purchasing, “Does it look good coming and going?” says Audrey Smaltz, who traveled alongside Mrs. Johnson as a sales coordinator. The director and producer chose bright, bold, and dynamic garments complimenting the melanated skin tones of her models, as black women would soon dominate the runways.

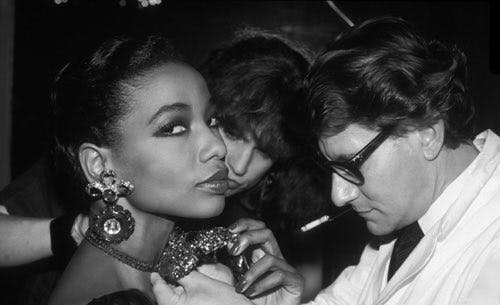

During the 1970s, Black women were at the height of fashion, as a surge of Black female models swept the runways, often beginning their modeling careers through the Ebony Fashion Fair. From Beverly Johnson, the first Black model to grace the cover of American Vogue, to Mounia, the Martinique-born haute couture model known for being Yves Saint Laurent’s muse. Black models became the commodity of the fashion world, as their ethnic features once shunned for consumption were now affirmed and embraced.

French designer Yves Saint Laurent and haute couture model Mounia pictured before a show (Courtesy of L’Officiel.com)

The models weren’t the only ones who stole the show, as Veronica Jones details the alluring flair of the traveling fashion show’s unique commentator, “The melodious, dramatic voice of the glamorous Audrey Smaltz captivated and enchanted the audience with vibrant intonations. She defined fabulousness for the world.” Smaltz would take to the main stage greeting show-goers until 1975, passing the baton to model and buyer Shayla Simpson, becoming the “voice and face” of the Ebony Fashion Fair until 1991.

This newfound cultural acceptance of black beauty and womanhood was also addressed within the cosmetics industry. In 1973, Fashion Fair Cosmetics, a product of Ebony magazine, was created for women of color when makeup companies largely ignored their existence. Regarded as the “Black Estée Lauder,” featured ladylike pink compacts, berry lipsticks, and frosty eyeshadows sold in major department stores, including A&S Brooklyn, Bloomingdales, Marshall Fields, and Harrods.

Advertisements for Fashion Fair Cosmetics, 1970s (Courtesy of Vintage Black Glamour by Nichelle Gainer)

Advertisements for Fashion Fair Cosmetics, 1970s (Courtesy of Vintage Black Glamour by Nichelle Gainer)

Acclaimed British model Naomi Campbell mentions taking care of her skin from an early age due to her Jamaican-British mother. “I used to sneak into my mother’s makeup bag [with] Fashion Fair and Flori Roberts, which were the only brands you could find then for dark skin,” recalls Campbell. Lauren Valenti. “Naomi Campbell’s Guide to a Glamorous 10-Minute Beauty Routine,” Vogue Magazine, June 2020, 1-2. Fashion Fair cosmetics celebrated the beauty and glamour of Black women in a variety of hues addressing a desire for representation, a model patterned by contemporary cosmetic brands such a Black Opal, MAC, and Fenty Beauty.

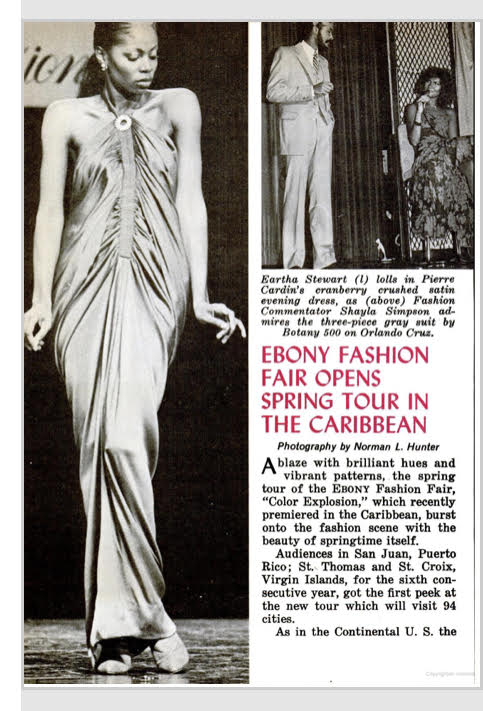

From cosmetics to the Caribbean, the Ebony Fashion Fair entered Bermuda, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands for their spring tour. “The Caribbean market loved us!” recalls Smaltz, as shows were hosted outside, providing a lush backdrop that included one model from the native island. The troupe of 13 models performed at various venues, including the Reichhold Center for the Arts, with proceeds going to the mentally and physically disabled of the island and the Peter Evelyn Scholarship Fund. Unknown. “Ebony Fashion Fair Opens Spring Tour in the Caribbean,” Jet Magazine, January 1980, 12-16.

“Ebony Fashion Fair Opens Spring Tour in the Caribbean,” Jet Magazine, January 31, 1980 (courtesy of Google Books)

The “Color Explosion” show featured vibrant patterns and brilliant hues inspired by the tropical climate, as models dazzled Caribbean audiences in ready-to-wear and haute couture garments. Valerie Hines glided across the stage in a three-tiered evening dress by Luis Fuentes of San Juan, while Avalon Jackson donned a Christian Dior batwing gown, captivating crowds. Ibid.

COLLECTOR’S EDITION: EBONY MAGAZINE, OCTOBER 1966

Eunice Johnson (1916 – 2010) created an archive of fashion garments, becoming both a fashion collector and an "unofficial fashion historian;" Aubry, Alex. “Chronicles of chic: Mrs. Eunice Johnson,” System Magazine, System issue No.1, 159. as her collection covered the gamut from Pierre Cardin to Rudi Gernreich. Many of these acquired garments were featured in Ebony Magazine and the Ebony Fashion Show; drawing your attention to three pheasant and peacock feathered headdresses featured in “Colorballoo,” Ebony Fashion Fair’s 1966 show, and the corresponding October 1966 issue of Ebony Magazine acquired by FIDM Museum. Two of the headdresses shown below are by Austrian-American designer Rudi Gernreich housed within FIDM Museum’s Rudi Gernreich archive. The famed designer was known for his avant-garde designs, including the “monokini,”and was regarded as one of the most innovative designers of the 1960s.

Ebony Magazine, “Ebony Fashion Fair Presents Colorballoo,” October 1966/FIDM Museum & Library

Detail of peacock feathered headdress

Detail of peacock feathered headdress

Rudi Gernreich peacock feathered headdress

Rudi Gernreich peacock feathered headdress

Rudi Gernreich pheasant feathered headdress

Rudi Gernreich pheasant feathered headdress

Detail of pheasant feathered headdress

Detail of pheasant feathered headdress

Both headdresses date to Fall 1966, and although unlabeled, are Layne Nielson for Rudi Gernreich. The headdresses were not available for resale–– they were only for the runway, and as such, one of the two pheasant examples was borrowed for the Ebony Fashion Fair. The pair of peacock headdresses were split between the Metropolitan Museum of Art and FIDM Museum, as Gernreich created two of every runway garment housed within his New York City and Los Angeles showrooms.

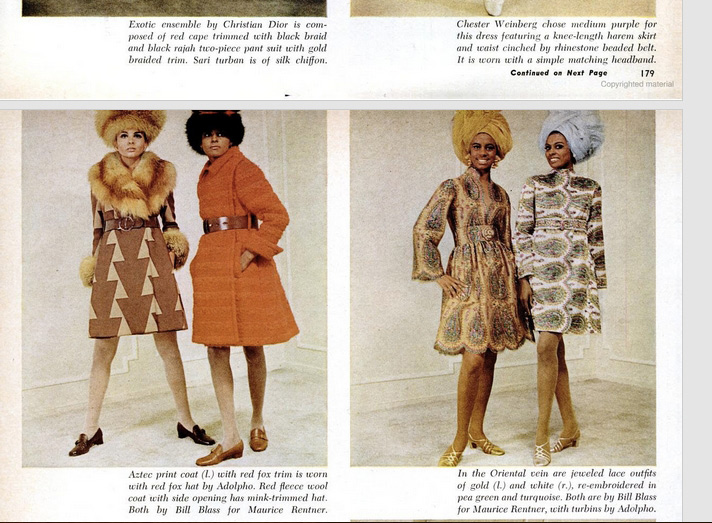

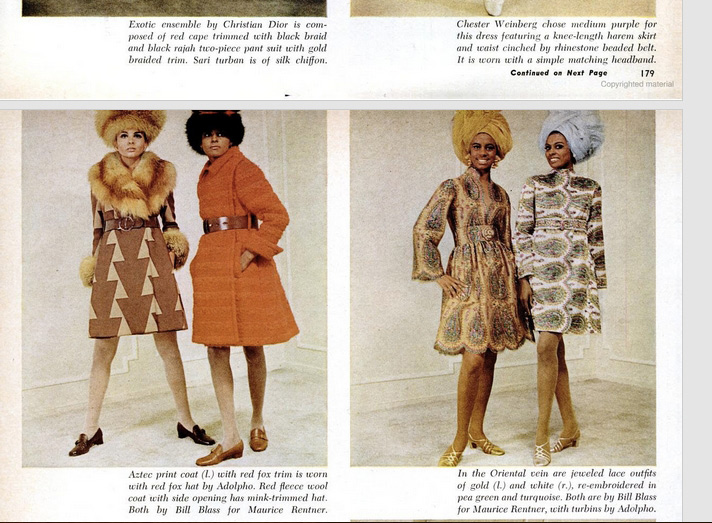

Another garment featured in Ebony Magazine, but not the fashion fair, is this gold mini dress (shown below) by fellow American designer Bill Blass. Blass' vision of style, innovation, quality, and practicality made him a standout contender during fashion's postwar scene. He created clothes with an American casual chic sensibility which offered women a modern sense of ease and comfort. After working closely with American designer Ann Miller and her brother Maurice Rentner, Blass began to develop his own clientele, and in 1970 he would buy the Maurice Rentner Ltd. and rename it Bill Blass Ltd. Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. "Bill Blass." Encyclopedia Britannica, June 2021. (shown in the tag) of the gold mini dress. Although this dress did not appear on the runway, this is an example of a piece that would have been available to purchase at a U.S. store or featured for editorial, such as the 1966 Ebony Magazine spread.

Ebony Magazine, “Ebony Fashion Fair Presents Colorballoo,” (Bill Blass gold mini dress on left), October 1966/FIDM Museum & Library

Ebony Magazine, “Ebony Fashion Fair Presents Colorballoo,” (Bill Blass gold mini dress on left), October 1966/FIDM Museum & Library

Figure 17: Bill Blass for Maurice Renter gold mini dress

Figure 17: Bill Blass for Maurice Renter gold mini dress

Figure 18: Garment tag, “Bill Blass for Maurice Rentner”

Figure 18: Garment tag, “Bill Blass for Maurice Rentner”

A LASTING LEGACY: 50 YEARS OF FASHION

During her 50-year reign in fashion, Eunice Johnson leveled the playing field, where both up-and-coming designers and established household names were seen as equals on the runways. The fashion maven engaged in the transformation of the fashion industry, launching the careers of black designers including Jon Haggins, Scott Barrie, Stephen Burrow, Patrick Kelly, Willi Smith, and many more, creating an avenue for black enterprise when mainstream fashion sought to negate their talent. The Ebony Fashion Fair essentially became the precursor for BIPOC designers such as Ghanaian-American designer Virgil Abloh to become the artistic director of French fashion house Louis Vuitton's menswear collection in 2018, while American designer Christopher John Rogers won the 2019 CFDA/Vogue Fashion Fund led by Anna Wintour, Global Chief Content Officer for Condé Nast.

In a full-circle moment, following in the footsteps of the late Jay Jaxon and Patrick Kelly, Haitian-American designer Kerby Jean-Raymond, creative director and founder of Pyer Moss, entered the world of haute couture in 2021 on his own terms–– creating a collection that paid homage to Black inventors. These successes weren't happenstance, as Ebony Magazine and the Ebony Fashion Fair shaped a new vision of Black America through contemporary fashion, formulating a more significant conversation around the complexities and acceptance of a race in greater American society. To quote the late American poet Maya Angelou, "Then Ebony arrived … to inform us and assure us that our lives were so important, they could never be edited out of the history of our people,” Unknown. "75 Years of Ebony Magazine," Smithsonian National History Museum of African American History & Culture as both Ebony Magazine and the Ebony Fashion Fair established systems of visibility, prominence, and ultimately spaces of Black joy.

Sources:

- Aubry, Alex. “Chronicles of chic: Mrs. Eunice Johnson,” System Magazine, System issue No.1, 156-167.

- Hall, Stuart. “Reconstruction Work: Images of Postwar Black Settlement [1984].” In Highmore, Ben (ed). The Everyday Life Reader. London and New York: Routledge, 2002, 262-272.

- Britannica, T. Editors of Encyclopedia. "Bill Blass." Encyclopedia Britannica, June 18, 2021. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bill-Blass.

- hooks, bell. “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” In Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. New York: The New Press, pp. 54-64.

- James, Frank. “Eunice Johnson Remembered For Linking Blacks, Fashion,” NPR, The Two-Way, January 5, 1-2. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2010/01/eunice_johnson_remembered_for.html

- Lewis D., Shawn. “Two Decades of Ebony Fashion Fair,” Ebony Magazine, December 1977, 146-148. https://books.google.com/books?id=7EJj7NQsAmYC&pg=PA146&dq=ebony+fashion+fair+Caribbean+spring+tour&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwifyqbUr73xAhU3l2oFHfcrCdkQ6AEwBnoECAoQAg#v=onepage&q=ebony%20fashion%20fair%20Caribbean%20spring%20tour&f=false

- Staples, Brent. "The Radical Blackness of Ebony Magazine: [Editorial]." New York Times, August 12, 2019, Late Edition (East Coast), pp. 1-4.

- Unknown. “Ebony Fashion Fair Opens Spring Tour in the Caribbean,” Jet Magazine, January 1980, 12-16.

- Unknown. “75 Years of Ebony Magazine,” Smithsonian National History Museum of African American History & Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/collection/75-years-ebony-magazine.

- Valenti, Lauren. “Naomi Campbell’s Guide to a Glamorous 10-Minute Beauty Routine,” Vogue Magazine, June 2020, 1-2.