Liberty London

A unique periwinkle afternoon gown stands in the flower-filled gallery of Fashion Philanthropy: The Linda & Steven Plochocki Collection. Its Japanese-imported gossamer silk textile and hand-embroidered English Tudor roses represent the distinct style of one maker: Liberty & Co., a brand synonymous with British heritage. The name immediately conjures images of the magnificent mock-Tudor emporium sprawling across London’s Regent Street – as much a part of the city’s landscape as Buckingham Palace.

Afternoon Gown, Liberty & Company, Ltd. c.1908 Loan courtesy of Linda & Steven Plochocki L2017.4.11AB

Afternoon Gown, Liberty & Company, Ltd. c.1908 Loan courtesy of Linda & Steven Plochocki L2017.4.11AB

Though Liberty has seen many changes in its one hundred and forty-two year history, it has maintained one core philosophy: Liberty is not merely a department store, but an emporium of rare goods carefully selected for the customer, as was the goal of its legendary founder Arthur Lasenby Liberty.[1] Liberty was born in 1843, the son of a draper in Buckinghamshire, and was just nineteen years old when he became a salesman at Farmer & Rogers’ Great Shawl and Cloak Emporium on Regent Street in London.[2] The year coincided with London’s famed International Exhibition, and the influence of the Japanese exhibits found its way into Farmer & Rogers, where Liberty was placed in charge of a new Oriental warehouse of exotic goods.[3] Ten years later, after being denied a promotion to partner, Liberty decided to open his own store.[4] In 1875, he opened a small location on Regent Street and sold imported textiles and Japanese curiosities.[5] A lover of the exotic, Liberty wanted to cater to the avant-garde and maintain a rare, exclusive, and unexpected selection of objects.

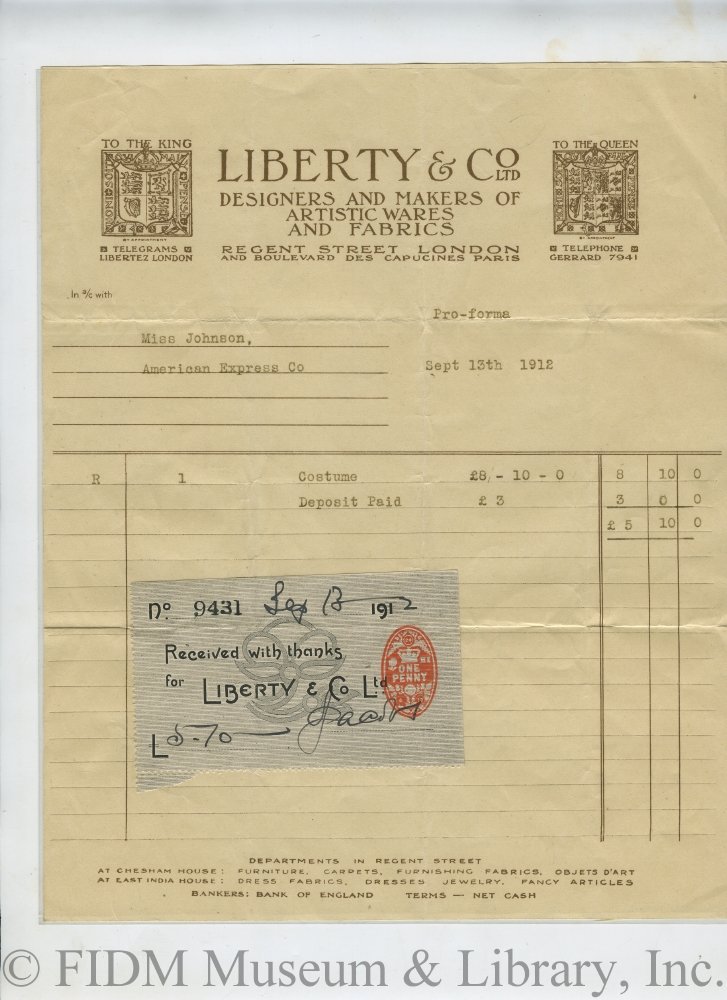

Single receipt from Liberty & Co Ltd. September 13, 1912 Museum Purchase SC2011.5.26

Soon his shop was frequented by William Morris, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, and other members of the progressive Aesthetic movement, a group who believed in 'art for art’s sake' and encouraged a return to antiquity in dress and craftsmanship.[6] Always a visionary in consumerism, Liberty recognized that middle and upper class women would also want to partake in the this movement, though perhaps to a lesser extent, and decided to “improve the nation’s taste by giving ordinary people the chance to buy beautiful things.”[7] Using imported Asian materials, such as the Japanese silk used in the Afternoon Gown on display in our galleries, he worked directly with English textile weavers and dyers to produce stronger colorfast fabrics in the artistic tones of sage green, mustard yellow, pale blue, light pink, and russet brown.[8] These shades became known as Liberty colors because of their close association with the store’s offerings.

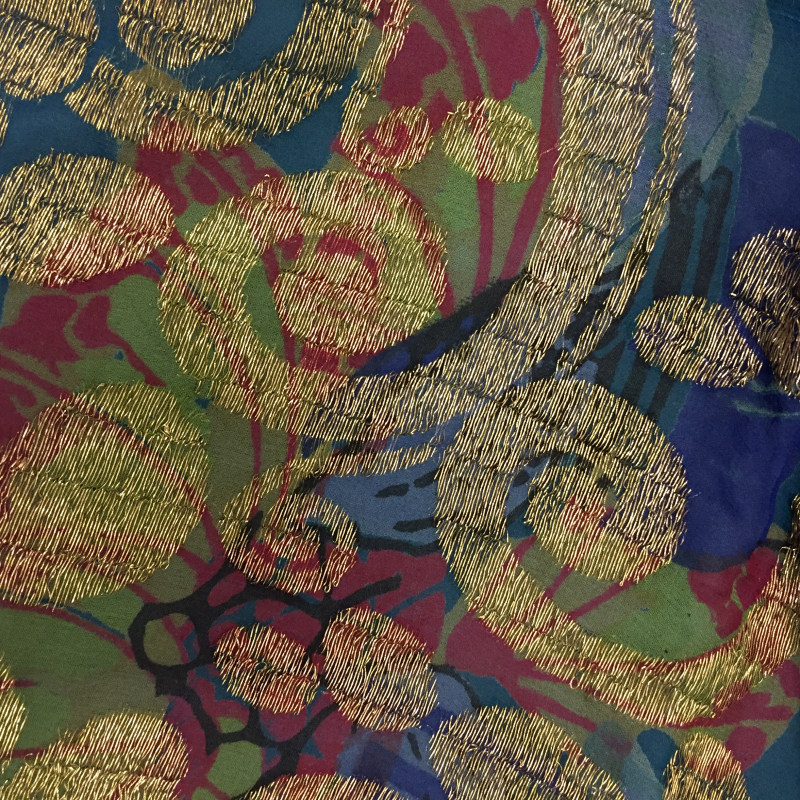

Fancy Dress Costume; textile attributed to Liberty & Company, Ltd. c.1895 Gift of Ron Bernstein 2011.1145.34

Fancy Dress Costume; textile attributed to Liberty & Company, Ltd. c.1895 Gift of Ron Bernstein 2011.1145.34

Liberty Art Fabrics grew in popularity throughout the eighteen-eighties and nineties and came to represent the English interpretation of Art Nouveau. Though Liberty kept their designers anonymous, respected artists such as Lindsay Butterfield, Harry Napper, and Thomas Wardle are known to have contributed to the innovative prints of this period.[9] One of the most recognizable prints in the Liberty archive was the result of a collaboration with Arthur Silver of Silver Studios, who created the Peacock Feather design known as Hera in 1887.[10] In order to capitalize on the growing appetite for Liberty fabrics, Arthur Liberty introduced an upholstery studio in 1882 and a costume department in 1884, which offered Aesthetic style loose gowns made with striking Liberty textiles.[11]

Cape attributed to Liberty & Company, Ltd. 1920s 2010.1101.1 Gift of Edward Bosley and Katherine Bennett in memory of Phyllis Bosley

Cape attributed to Liberty & Company, Ltd. 1920s 2010.1101.1 Gift of Edward Bosley and Katherine Bennett in memory of Phyllis Bosley

In the early twentieth century, the store went through a massive renovation to build the Tudor façade that is now the visual icon of the Liberty brand. Arthur Liberty wanted to celebrate the merchant spirit of the Tudor era, and felt his store, which carried many hand-made and high quality items, was closely linked to the craftsman guilds and exotic trading routes of that period.[12] The dark wood beams and old-world aesthetic also lent an intimate and mysterious atmosphere to the building, separating it from the common department store shopping experience; goods could be displayed in small areas, almost like the rooms of a home.[13] Arthur Liberty was ingenious in visually distinguishing Liberty from other British brands – the building decisively establishes the store as a site of English heritage. To add to its royal luster, King George V and Queen Mary formally opened the new location on June 24, 1927.[14] The Art Nouveau style was considered passé by the late Edwardian era, but Arthur Liberty’s unique understanding of his consumer allowed the store to adapt to changing tastes in design. Liberty Art Fabrics produced new prints that were “firmly rooted in a vision of English country life,”[15] and the inter-war years saw the production of vibrant yet traditional floral designs. Head cotton buyer William Haynes Dorell introduced Tana Lawn cotton prints adorned with dainty florals in the nineteen-thirties, which immediately became best-sellers – even Princesses Elizabeth and Margaret had dresses of the fabric.[16] These small floral prints remain closely associated with the Liberty name, and are used in the majority of its twenty-first century design collaborations.  Pocket Square, Liberty & Company, Ltd. c. 1990 Gift of Joan Worth in memory of Marvin Worth S2006.890.1378

Pocket Square, Liberty & Company, Ltd. c. 1990 Gift of Joan Worth in memory of Marvin Worth S2006.890.1378

The nineteen-fifties introduced a revival of Liberty prints that renewed interest in the brand. William Poole, an assistant designer in Liberty’s Merton Abbey printworks, viewed a small Art Nouveau exhibition in Paris in 1958, and he astutely sensed that prints in the Liberty archive would coincide with the new taste for swirling patterns and psychedelic color schemes.[17] Poole adapted Liberty’s Art Nouveau prints to a silk-screening process and produced updated colorways in silk, wool, and organza.[18] The resulting textile collection, named Lotus, was released in 1960 and was universally embraced by couturiers. Fabrics from Lotus featured in many of the top haute couture collections of the season: Jean Muir, Mary Quant, Victor Stiebel, Bill Blass, Halston, Cacharel, Yves Saint Laurent, and Arnold Scassi all utilized Lotus fabrics in their designs. The success of Lotus encouraged a new era of collaboration between Liberty and the top fashion designers of the fifties, sixties, and seventies. The store celebrated its centennial in 1975, but in the following decades Liberty became a tired and old-fashioned commodity. It took a change in leadership and new sales tactics to revive the brand; embracing Liberty’s distinct design legacy with high-end collaborations recast the store as “surprising, cool and aspirational.”[19] From 2007 to 2014, Liberty instituted over twenty-five design partnerships with fashion brands, from Hermes to Dr. Martins. The store has recruited a new generation of consumers by embarking on unique and unexpected collaborations, thus asserting its place in British heritage while remaining relevant in the retail industry.

[1] Fletcher, 2003. [2] Arwas, 1. [3] Adburgham, Biography of a Store, 13. [4] Ibid., 17. [5] Ibid., 20. [6] MacCarthy, 2011. [7] Adbrugham, Liberty of London, 31. [8] Chrisman-Campbell, 45. [9] Harris, 54. [10] Arwas, 4. [11] Chrisman-Cambell, 46. [12] Adburgham, Biography of a Shop, 108. [13] Ibid. [14] Ibid. [15] Calloway, 129 [16] Adburgham, Biography of a Shop, 121. [17] Bayer, “An Era of Revivals,” 174. [18] Ibid., 175. [19] Hall, 2008.