La Dolce Vita

La Dolce Vita evokes beauty, luxury, and joyful exuberance – mid-century Italian life at its most glamourous. We think of Sophia Loren wearing lavish gowns at movie premieres, and European royalty vacationing on the Amalfi coast. Yet just a few years earlier, Italy was suffering the aftermath of World War II, surrounded by destruction and struggling to find a national identity after years of dictatorship.[1] Surprisingly, Italian fashion played a vital role in the country’s post-war economic resurgence.

From Prada to Pucci, Valentino to Versace, Italy is heralded as one of the most progressive and respected fashion capitals in the world. However, the country was not always regarded as a fashion hub. In the years prior to World War II, Italy, like most countries, followed the fashion barometer set by haute couture designers in Paris. The Italian fascist regime sought to establish a unified la linea Italiana (Italian style)[2] in dress during its twenty-year reign with little success, and Dior’s tremendously successful New Look collection in 1947 ensured all eyes remained on Paris.[3] Thus, the country’s designers continued to look to France for guidance immediately following the war.

It took the efforts of one man, Giovanni Battista Giorgini, to push Italian design into the international spotlight. Giorgini recognized the quality and talent of post-war Italian fashion and industrial design. He wanted to promote the Italian aesthetic outside of France’s influence, celebrating his country’s fine craftsmanship and quality textiles. A former fashion buyer with American connections, Giorgini knew that capitalizing on the U.S. market was the answer to success for Italian design.[4] The Marshall Plan, the U.S. economic aid package to Europe, insured that both governments were willing partners in supporting local industry.

Italian Fashion show at Sala Bianca, July 1955; courtesy of Archivio Giorgini.

Italian Fashion show at Sala Bianca, July 1955; courtesy of Archivio Giorgini.

In February 1951, Giorgini utilized his contacts and organized a small fashion show for American buyers and journalists featuring Italian designers.[5] The intimate gathering was held at his home in Florence, Villa Torrigiani. The show was such a triumph, he promptly held a larger event in July 1951 at Florence’s Grand Hotel – again, the show was met with enthusiastic reviews from the American contingency. Giorgini’s campaign for Italian fashion was an unequivocal success, and U.S. department stores such as I. Magnin began importing everything from Italian resort wear to wasp-waist, full-skirted gowns. Thanks to Giorgini, clothing exports grew exponentially, increasing over 150 percent from 1950 to 1957.[6] His fashion shows continued annually at Palazzo Pitti’s striking Sala Bianca from 1952 to 1982.

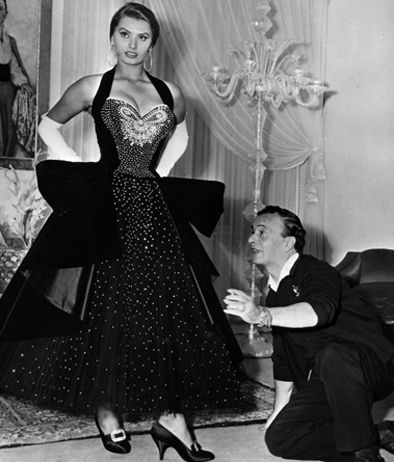

Emilio Schuberth and Sophia Loren, courtesy of Sky Mag.

Emilio Schuberth and Gina Lollobrigida, courtesy of Aol.com.

As Giorgini highlighted Italian fashion on the international scene, the world of cinema also discovered the country’s artistic appeal. Lower costs enticed Hollywood to move more productions abroad, while Italian filmmakers used cinema to explore the country’s developing post-war identity.[7] A new ideal of Italian beauty and lifestyle emerged from this cinematic resurgence; la Bella figura represented Italy’s “sensuality, grace, and love of leisure,”[8] embodied onscreen by the smoldering sexuality of actresses such as Sophia Loren and Gina Lollobrigida. Now global celebrities, these actresses relied on Italian designers to provide glamorous movie-star wardrobes. Enter Emilio Schuberth, one of the pioneer designers included in Giorgini’s original fashion shows, and a man who recognized the reciprocal relationship between Italian fashion, film, and celebrity.

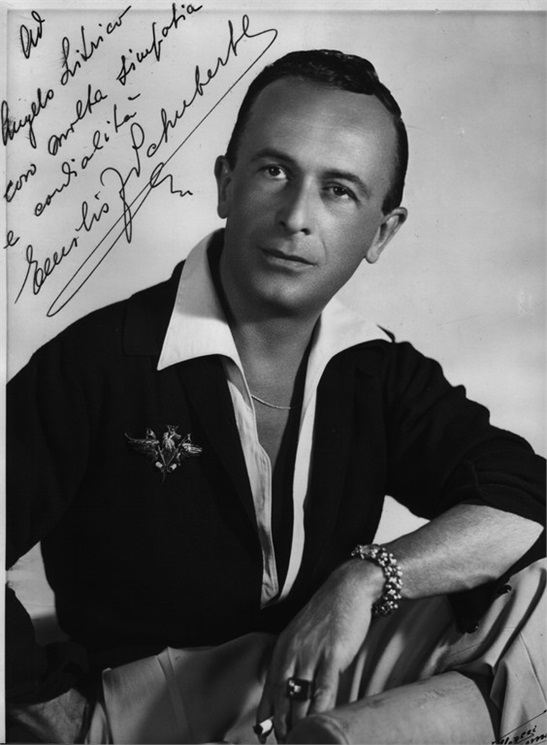

Emilio Schuberth, courtesy of Vogue Italia.

Schuberth, born in Naples in 1904, studied painting before moving to Rome as a young man.[9] He began his career making ladies’ hats, and later opened his own atelier in 1939.[10] Schuberth was an unapologetically extravagant designer. Luxury textiles, dramatic color combinations, embroidery and embellishment became his hallmarks; The New York Times compared his work, not unkindly, to a cake, “lovely, gooey, cream-filled, icing topped.”[11] Above all, he was known for his celebration of the female form: tiny waists and voluminous skirts, a visual interpretation of Italy’s la bella figura. Schuberth cultivated the persona of an eccentric designer, wearing jewels and giving his designs whimsical names such as 'Schuberth's Heart,' 'Grandmother was Right,' and 'Summer at the Pole.'[12] He gained a loyal following after designing Princess Maria Pia di Savoia's wedding dress in 1955. Actresses adored his luxurious designs – perfect for the fantasy world of entertainment – and he provided wardrobes for both Loren and Lollobrigida.

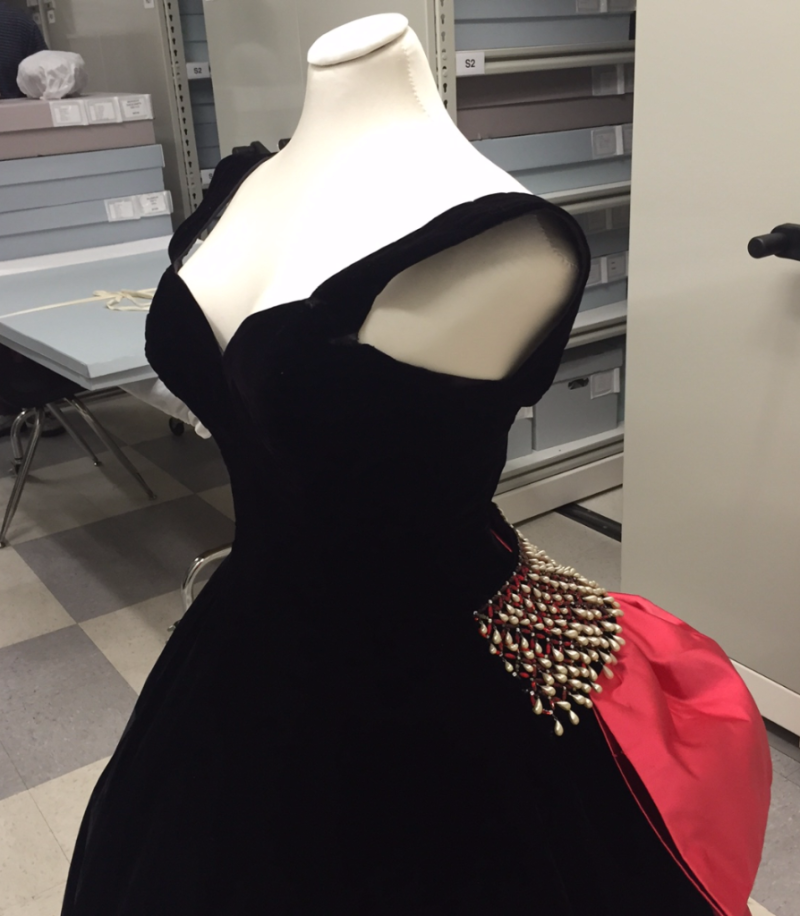

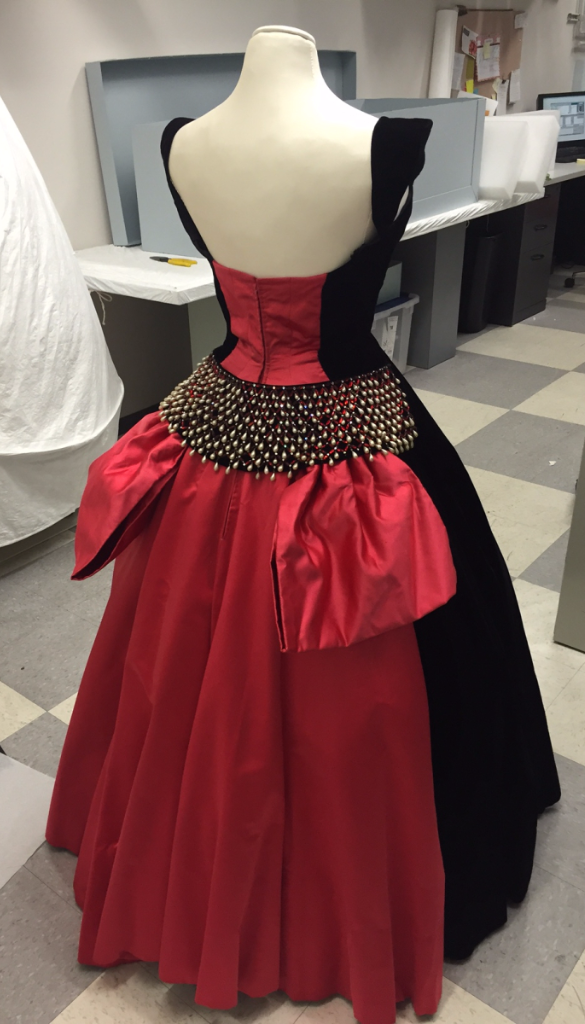

The FIDM Museum Schuberth gown on display at the McCord Museum, Montreal in The Glamour of Italian Fashion: 1945 - 2014.

The Victoria & Albert Museum explored Italian identity through fashion with their 2014 exhibition The Glamour of Italian Fashion: 1945 - 2014. Now on display at the McCord Museum in Montreal, the FIDM Museum was asked to loan an extravagant Schuberth gown to the exhibition. The ballgown is a study in contrasts: black velvet and bright pink satin with rhinestones and pearl beading, it showcases Schuberth’s love of opulence and understanding of a woman’s form. Schuberth himself said of his designs, “All I do is cover the most beautiful invention, the most curvaceous sculpture that God has placed on this earth: the body of woman.”[13]

[1] Sonnet Stanfill, The Glamour of Italian Fashion: 1945 – 2014 (London: V&A Publishing, 2014), 16.

[2] Nicola White, Reconstructing Italian Fashion: America and the Development of the Italian Fashion Industry (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2000), 76.

[3] Ibid., 77.

[4] Stanfill, The Glamour of Italian Fashion, 12.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Tamsin Blanchard, “Bella Figura: behind the Glamour of Italian Fashion at the V&A,” Telegraph.co.uk, March 15, 2014, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/luxury/womens-style/27552/bella-figura-behind-the-glamour-of-italian-fashion-at-the-va.html.

[7] Francesca Iorio, “Emilio Federico Schuberth,” Vogue Italia, http://ow.ly/pr3N3026Nih.

[8] “Evening Ensemble,” MetMuseum.org, http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/C.I.55.76.12a-d/.

[9] “Emilio Schuberth, a Couturier in High-Fashion, Dies in Rome,” The New York Times, January 6, 1972, page L41.

[10] Gloria Bianchino, ed., Italian Fashion, Volume 1: The Origins of High Fashion and Knitwear (Milan: Electa, 1987), 257.

[11] Carrie Donovan, “Fashion Trends Abroad,” The New York Times, January 22, 1959, page L35.

[12] Bianchino, Italian Fashion, 257.

[13] Ibid., 14.