Intern Report: Raymond Duncan

The FIDM Museum was thrilled to host the CSA Western Region Jack Handford Summer Scholarship winner, Axelle Boyer. A Ph.D. student in History of Art and Visual Culture at UC Santa Cruz, Axelle previously received her M.A. in Fashion Studies from Parsons School of Design. Her research interests include body adornment, style, and fashion of the African diaspora. Axelle spent her time at the Museum working with our Special Collections, and in the process discovered an intriguing booklet by artist Raymond Duncan. Below, Axelle delves into Duncan’s fascinating world – including his foray into garment and textile design.

****************************************************************************************************************

“Make Yourself in Working:” Raymond Duncan and the Art of Living

In August 2018, while working in the FIDM Museum’s Special Collections, I came across a brochure that didn’t quite fit in with the collection of glossy ephemera that I was processing at the time. The collection in question included archival issues of Vogue, Chanel catalogs, and backstage photographs of 90s supermodels. The object at hand was a small booklet made of loose and yellowed pages with abundant writing and a few illustrations.

Booklet Raymond Duncan Winter Exhibition of Parisian Art 1910-1920 FIDM Museum Purchase, SC2017.5.96

A quick Google search informed me that Raymond Duncan (1874 - 1966) was the brother of renowned American dancer Isadora Duncan (1877 or 1878 - 1927). Born in San Francisco, the brother and sister had relocated to Europe in the 1890s – like many of their compatriots at the time. While Isadora rose to fame as one of the pioneers of modern dance, Raymond became a prolific painter, poet, playwright, actor, and a proud advocate of weaving, printing, sandal-making, and vegetarianism. In 1911, he opened a school on Paris’ Left Bank, called the Akademia Raymond Duncan, where he taught free courses in the various arts and crafts that he had honed, gave philosophical lectures, and staged plays. The brochure opened with a short biography of artist Raymond Duncan, and went on to provide curious and dithyrambic descriptions of his art works. The disparate assemblage included 15 “brush-dyed” and block-printed textiles classified under the category “Paintings;” a “series of studies,” which were also block-printed and “dyed in by brush” on various textiles; seven woven rugs; and 13 books under the category “Book-printing.” The brochure was actually a self-published catalog attesting to Duncan’s multimedia endeavors, and had seemingly been written by the artist himself.

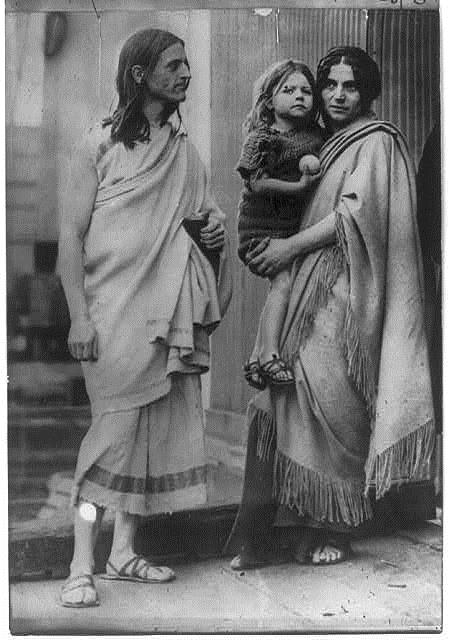

Raymond Duncan with his wife and child 1912 Bain News Service, N.Y.C. Library of Congress

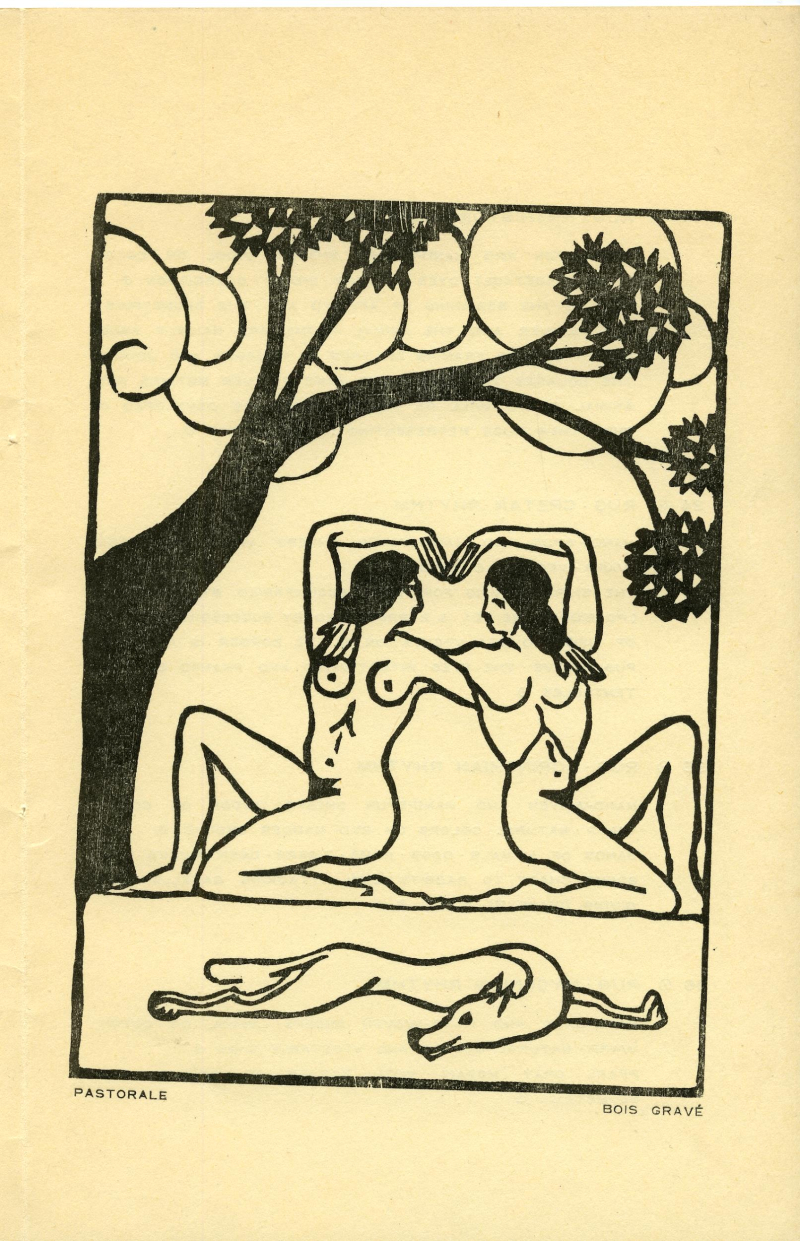

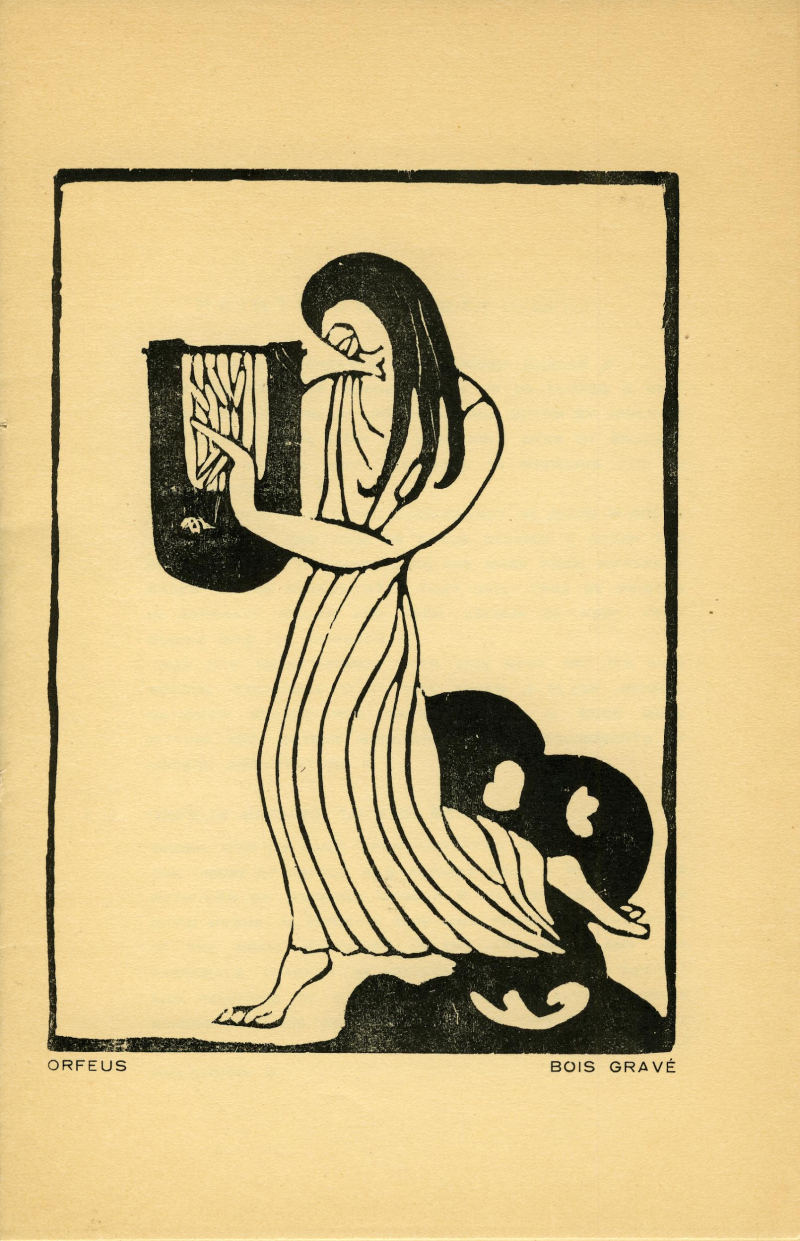

It wasn’t so much the text of the catalog that intrigued me, but rather the exquisite prints that adorned its pages. The three illustrations were block-printed on paper using a carved wood block (“bois gravé”). Art Nouveau influences are manifest in the curvilinear lines of the dreamy forms and bodies represented. The figures were also reminiscent of the flowing movements of Isadora Duncan’s modern dance, while the titles of the pieces – “Orpheus,” “Pastorale” – referenced ancient Greek literature and mythology.

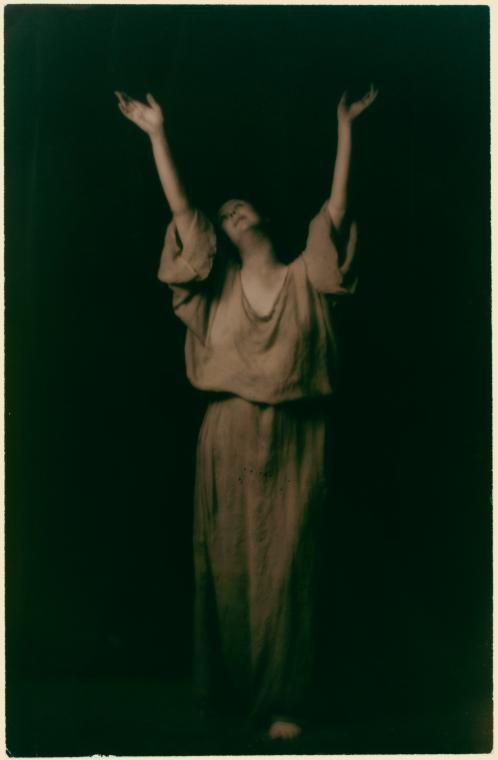

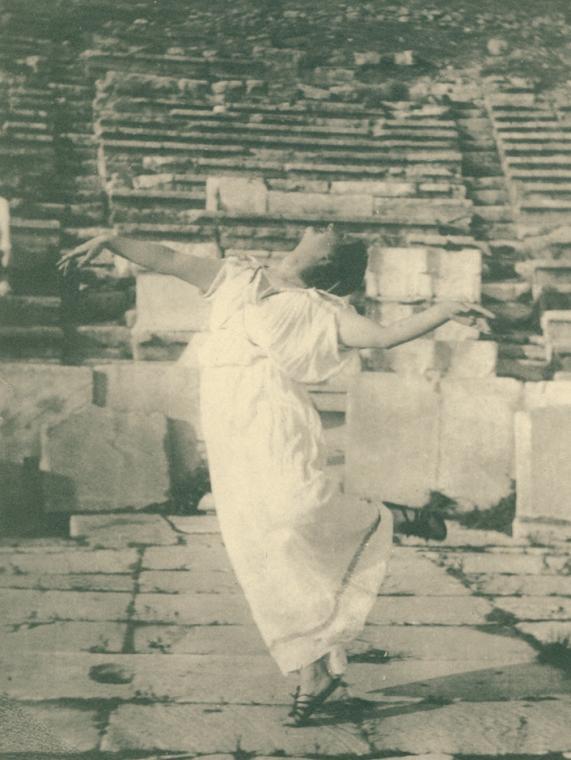

"Isadora Duncan: studies" Photograph by Arnold Genthe 1915-1918 Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections

Raymond Duncan Winter Exhibition of Parisian Art Pastorale, 1910-1920 Wood block print on paper FIDM Museum Purchase, SC2017.5.96

Raymond Duncan Winter Exhibition of Parisian Art Pastorale, 1910-1920 Wood block print on paper FIDM Museum Purchase, SC2017.5.96

Raymond Duncan Winter Exhibition of Parisian Art Orfeus, 1910-1920 Wood block print on paper FIDM Museum Purchase, SC2017.5.96

Raymond Duncan Winter Exhibition of Parisian Art Orfeus, 1910-1920 Wood block print on paper FIDM Museum Purchase, SC2017.5.96

I was fortunate enough to find that the FIDM Museum owns two garments made by Raymond Duncan. Analyzed in conjunction, the brochure and the garments start making sense of each other – and allow me in turn to highlight the ways in which text can inform and enrich our study of garments.[1] The first Duncan piece acquired by the FIDM Museum is a light grey-pink tunic made of a rectangular piece of silk and wool crepe with a center slit for the neck. The neck and shoulders are adorned with bands of purple, gold, green, and blue geometric motifs (zigzags and diamonds). On the length of the tunic, these alternate with bands of leaves and berries. The garment displays deliberate simplicity in its line and construction: it presents no seam or hem, and its bottom edge is frayed while its unsewn sides hang open.

Tunic Raymond Duncan, 1915-1920 Wool silk/crepe with vegetable dyes FIDM Museum Purchase: Partial funds provided by FIDM/Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising, 2008.905.1

Tunic Raymond Duncan, 1915-1920 Wool silk/crepe with vegetable dyes FIDM Museum Purchase: Partial funds provided by FIDM/Fashion Institute of Design & Merchandising, 2008.905.1

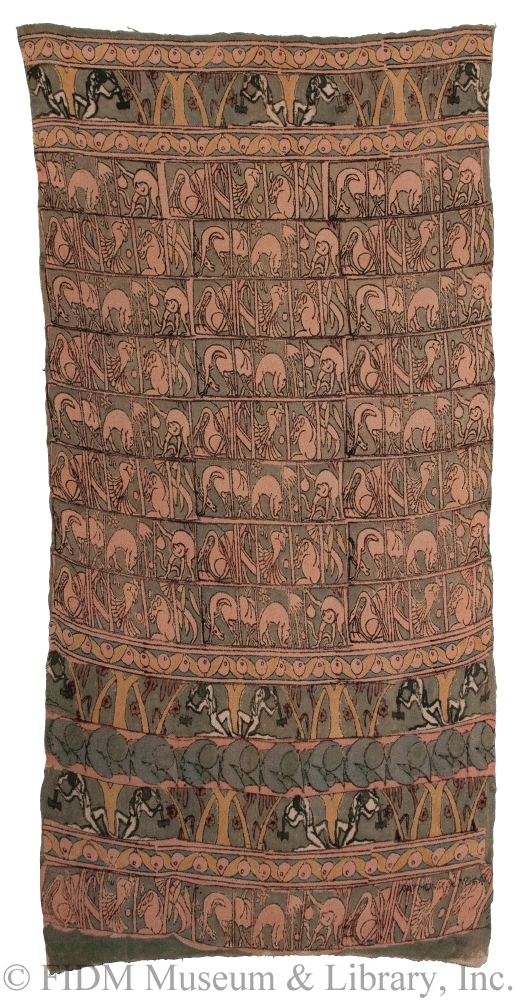

Raymond Duncan signature on tunic The second piece is a textile panel of wool and silk plain weave with crepe yarns, with pink, brown, and yellow motifs on a dark green background. The motifs are represented within a grid composed of 17 horizontal bands: 8 bands depicting various animals alternate with bands of figures chopping wood, alongside a repeating frieze of interlaced berries and leaves.

Textile Panel Raymond Duncan, 1915-1925 Wool silk/crepe with vegetable dyes FIDM Museum Purchase, 2009.5.49

Detail of textile panel The motifs on both pieces were block-printed and colored using natural dyes.

Detail of textile panel The motifs on both pieces were block-printed and colored using natural dyes.

The brochure provides an insight into what Duncan called a “new school of painting” on fabrics, “midway between fresco and tapestry.”* Colors, he explains, were “dyed in by brush,”* and since natural dyes cannot be mixed in order to achieve a specific tone, each tone was painted in separate fields – hence explaining both the grid-like layout and the approximate color filling of the motifs. The textiles were presumably hand-woven since Duncan prided himself in spinning and weaving his clothes. Both the textile panel and the tunic bear witness to Duncan’s fascination with Ancient Greece, whose culture he carefully studied at the Louvre in Paris, and, later, in Greece, where he lived for several years. The motifs painted on the textile panel present a striking similarity with ancient Greek ceramics.

Terracotta neck-amphora (jar) with lid and knob Archaic period, ca. 540 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.230.14a, b

Terracotta neck-amphora (jar) with lid and knob Archaic period, ca. 540 B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.230.14a, b

Duncan’s tunic is reminiscent of the chiton, a classical Greek garment that consisted of a rectangular piece of fabric “pinned or sewn at the shoulders and usually girded around the waist,” and also involved minimal construction (Metropolitan Museum of Art, Department of Greek and Roman Art 2003).

Duncan’s pieces, however, were not meant to be exact replicas of ancient Greek attire. Duncan “retained the skeleton of the classic and from it developed an interpretation of striking modernism.”* Above all, his designs speak to the time and place in which he evolved. While his work drew from Ancient Greece for inspiration, his aesthetic artfully blended the curved lines of Art Nouveau with the more modern and geometric aesthetic of the Art Déco movement (Martinelli 2013). Duncan was perhaps also influenced by the values of the Aesthetic movement. In the late 19th century and early 20th century, the Aesthetes - the intellectuals and artists who formed the Aesthetic movement - rejected the fashions that emerged from the Industrial Revolution, deploring sameness and the poor quality of mass-produced goods. They sought to return to the aesthetic of the Antiquity and the Renaissance and to “old-fashioned methods of clothing production: the use of natural dyes, handlooms and such hand-worked details as smocking and embroidery” (Takeda 2010). Many of Duncan’s contemporaries, such as Paul Poiret (1879-1944) and Madeleine Vionnet (1876-1975), were influenced by the reforming spirit of this aesthetic revolution, and attempted to break with the corseted body ideal of the Victorian and Edwardian periods. In addition, Duncan had a paramount interest in movement – a concern he shared with his sister Isadora. His work testifies to his vision of a modern body that would be free of constrictions. His tunics, for instance, are soft and fluid, allowing for an extended range of movements.

"Duncan in outdoor theater at Acropolis," Photographer unknown 1910-1927 Jerome Robbins Dance Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections

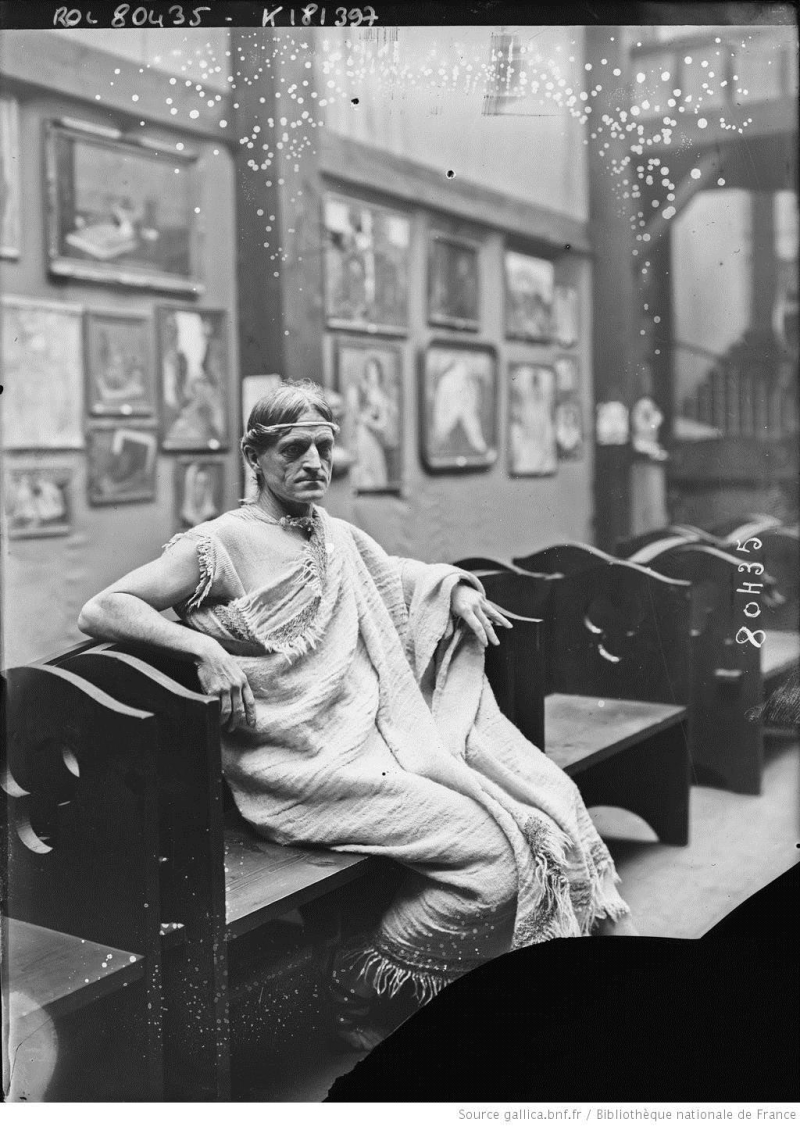

Yet, Duncan can hardly be compared with such contemporaries as Poiret or Vionnet. Even though he resided in the epicenter of fashion and sold handmade luxury pieces to an elite clientele in New York and Paris, Duncan cannot be called a couturier in the Parisian sense. Indeed, Duncan’s primary purpose wasn’t to create fashionable garments, but rather to achieve self-sustainability through a return to prior modes of clothing production. “The principle is this: make everything that you need, for yourself, and attempt to not need what you cannot make,” he declared in a 1955. After the First Balkan War (1912-1913), Duncan taught his craft to Albanian refugees, helping them become “self-supporting on the products of the arts and craft work.”* In the midst of World War II (1939-1945), he refused to leave Paris when Hitler occupied it and kept his school running. The Los Angeles Times reports that he “taught 10,000 people to spin, weave and knit wool from their mattresses.”[2] Duncan’s uniqueness resided in his fierce independence from conventions. He proposed a radical approach to art as an all-encompassing, holistic practice, refusing to discriminate between artistic forms and disciplines. For Raymond Duncan, writing a book had the same value as book printing. He considered fashion in particular as an art form in its own right. Duncan painted on fabrics as if they were canvases, signing his name at the bottom of his garments – in place of a label. By doing so, he elevated dress making to the status of painting (which, at the time, was considered fine arts and thus superior to fashion). Moreover, Duncan was radical enough to turn his nose up at conventions of dress, for he wanted people to “see the man and not the clothes” (as per his interview with Orson Welles). Throughout his life, he sported long hair and rejected stiff menswear if favor of his own unisex tunics and hand-made leather sandals – at the risk of scandalizing his contemporaries.

Raymond Duncan 1923 Photographies de l'Agence Rol Bibliothèque nationale de France

Raymond Duncan 1923 Photographies de l'Agence Rol Bibliothèque nationale de France

And indeed, in 1910, in New York, Duncan’s young son Menalkas was reportedly taken away from his family. The police considered that he wasn’t wearing proper clothing for the winter. Headlines spoke of the “sartorial disturbance” provoked by the parents’ “breezy costumes.”[3] Raymond Duncan certainly lived up to his motto: “make yourself in working.” Whether he inspired irony, contempt, or admiration, his contribution to aesthetics should be recognized, for he created a total system where text and textiles corresponded, and art and life converged. Bibliography Department of Greek and Roman Art. “Ancient Greek Dress.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2000–. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/grdr/hd_grdr.htm (October 2003) Martinelli, Megan. “"Would Live Like Ancient Greeks": The Art and Life of Raymond Duncan.” Thesis, University of Rhode Island, 2013. Monk, Craig. Writing the lost generation : expatriate autobiography and American modernism First edition. Iowa City, IA: University of Iowa Press, 2008. Palmer, Alexandra. “'At Once Classical and Modern': Raymond Duncan Dress and Textiles in the Royal Ontario Museum,” in Dress History: New Directions in Theory and Practice (2015): 127-143. Takeda, Sharon Sadako., Spilker, Kaye Durland., Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly., Esguerra, Clarissa M., and LaBouff, Nicole. Fashioning fashion : European dress in detail, 1700-1915. Los Angeles: Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2010. Welles, Orson. Around the World with Orson Welles, 1955. [1] Throughout this article, quotes from Duncan’s catalog will be marked with an asterisk*. [2] “Eccentric U.S. Artist Duncan Dies in France,” Los Angeles Times, Aug 17th, 1966. [3] “BARE-LEGGED BOY SHOCKS A POLICEMAN,” New York Times, January 9th, 1910. this is a link to Orson Welles' documentary featuring Raymond Duncan. Should I delete the link?