Intern Report Part Two: The Dress Detective

We are so excited to share Part Two of intern Kasia Stempniak's blog series; in this post, she shares her findings after completing The Dress Detective method on a 19th century Parisian couture gown. Make sure you read Part One about Kasia's summer internship at the FIDM Museum!

*******************************************************************************************************

I always saw, I always said

If I were grown and free,

I’d have a gown of reddest red

As fine as you could see,

Dorothy Parker’s poem of sartorial bliss in a red dress might have resonated with the owner of the vibrant velvet gown below.[1]

Velvet Evening Gown, P. Barroin

Velvet Evening Gown, P. Barroin

Paris, France, c. 1897

Gift of Jane Riggs

2013.1098.1

This gown is one of four pieces in the FIDM Museum’s permanent collection attributed to the Parisian dressmaker P. Barroin. In my last post I discussed learning about object handling and research during my internship at FIDM. In this post, I apply what I learned to this exquisite French gown using the three steps set out by the book The Dress Detective.

*This post will be an abridged version of the method.

Step 1: Observation

This first step involves taking notes, photographs, and/or sketches in order to record as much information as possible regarding the garment’s textiles, labels, measurements, and construction. The idea is to walk away from the garment with a comprehensive “visual image” of it.[2] The gown I examined is a one-piece evening gown in a bold red silk velvet. It has a center-front opening with hooks and eyes and “leg of mutton” sleeves. The interior features a pale red silk taffeta lining and a petersham label with the name P. Barroin and the address ‘394 rue St Honoré Paris’ stamped in gilded letters.

There is boning in the interior of the bodice with hand overcast seams. The bodice waist measures 28 inches and the bust comes in at 42 inches. Several areas of the gown indicate alterations were made: the interior lining has a patch of a different shade of red near the center-front opening, suggesting it was let out. The skirt’s major vertical seams also show evidence that they were let out, possibly during the fitting stage.

A small sachet, about an inch wide and long, is sewn into the interior of the proper left side of the bodice.

The shoulders on the bodice feature an elastic band, probably sewn in to compensate for the heaviness of the sleeves.

Step 2: Reflection

During this phase in the case study, the researcher reflects on the empirical information recorded during observation in a more sensory and personal manner. This particular gown is in very good condition and very well-made. Its low-cut neckline, coupled with the sumptuous velvet fabric, suggests the gown would have been worn to a formal evening function. The garment also exemplifies how fashion and the sensorial fuse. Visually, the monochromatic red and the train of cascading velvet is stunning; velvet, under the artificial lighting of the fin de siècle, would have shown off different light reflections and shades.

The wearer of this garment was certainly not afraid to make an entrance and stand out. In addition to the aural quality the gown would have had with its rustling silk velvet, the piece also includes evidence of an early type of deodorizing technology. The square sachet embedded in the bodice, which appears in two other Barroin gowns in the Museum’s collection, would have been filled with some sort of pulverized scent that would be released once in contact with the wearer’s body. These sachets can be found in late nineteenth-century bodices and are a reminder that garments are not disembodied objects but rather, as Mida and Kim point out, “a form of material memory carrying the imprints of its intimate relationship to the body.” [3]

Step 3: Interpretation

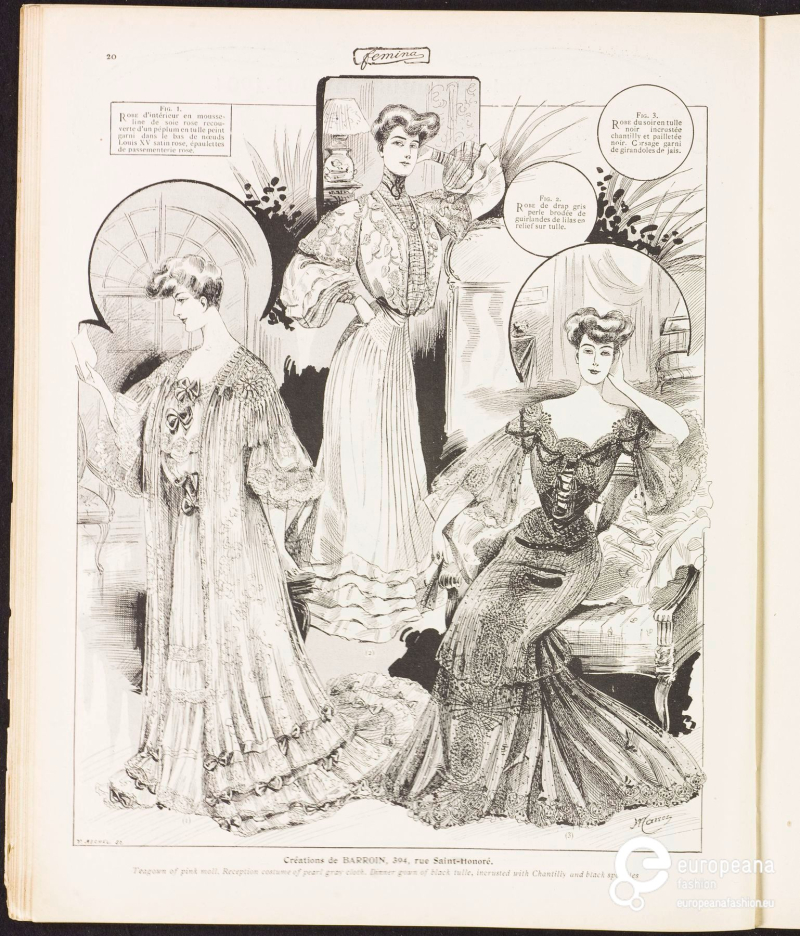

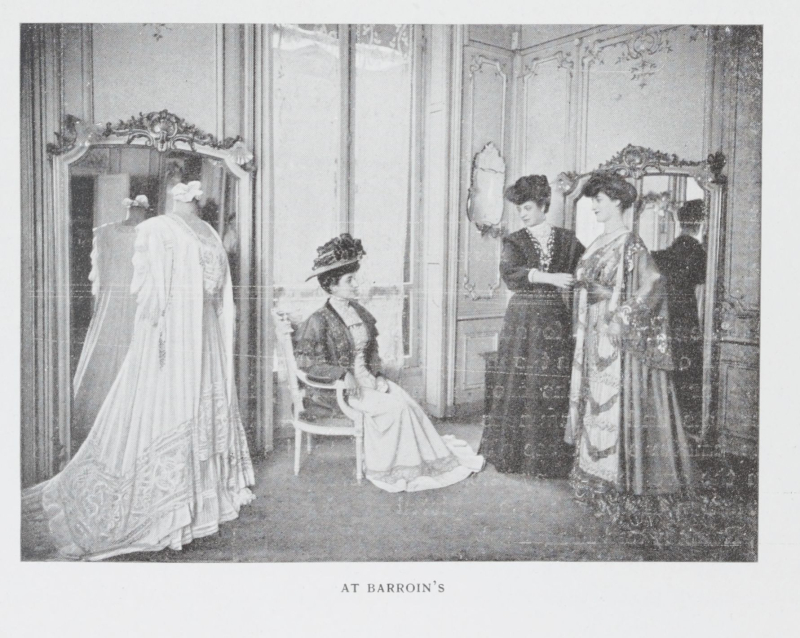

Interpretation involves researching the history of the garment (e.g. donor history, if available) and/or label history in order to give social, economic, and historical context to the object. After consulting fashion plates and looking at the different sleeve fads of the 1890s, I settled on a date range of 1894-1896 for the gown. Unfortunately, donor history revealed very little, except that the gown and the other Barroin pieces (all the same size) were found in a trunk in a home being torn down in the beach town of San Diego, California. Wealthy Americans often bought from Parisian dressmakers in the 19th century so it is likely the owner of this gown chose Barroin as her fashionable outfitter, even when residing or vacationing in the far away resort town of San Diego. Barroin’s label address was a clue that he was part of a network of top Parisian dressmakers since rue Saint-Honoré was located in the swanky first arrondissement or district in Paris, home to designers like Worth and Doucet as well as other luxury goods stores like Guerlain. Even though a simple Google search revealed little about Barroin, I started digging into the digitized archives of the Bibliothèque Nationale de France, which proved very useful. There were dozens of mentions of Barroin in newspapers and fashion journals from the early 1890s up until the early 1920s. One of the earliest appearances of the name Barroin and the address 394 rue Saint Honoré is in an advertisement from 1892 in the French journal Chronique artistique. [3] Although in the advertisement Barroin appears as ‘C. Barroin,’ subsequent mentions and advertisements refer only to a “P. Barroin,” with the ‘P’ standing for Paul. Married to a Madame Reinach, Paul Barroin and his wife worked together until her death in 1906 (her funeral was attended by their highly fashionable clientele).[4] After her death, the fashion house continued to thrive and appeared in issues of Le Figaro and Fémina.

Femina, November 1, 1903, via Europeana

Femina, November 1, 1903, via Europeana

Barroin’s participation in the Paris Exposition of 1900 testifies to his reputable position in haute couture during the Belle Époque. He was one of twenty designers who were members of the Chambre syndicale de la haute couture whose gowns were featured in the Exposition’s Costume Palace. Below is a print of a Barroin tea gown from Les Toilettes de la Collectivité de la Couture, Les Ches d’Oeuvre à l’Exposition Universelle Internationale de 1900, a folio that included illustrations of the gowns displayed at the Exposition.

‘Barroin 1900,’ Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Costume and Textiles Department

Le Bulletin du Norddeutscher Lloyd de Bremen, Nov. 1907 (Vol. 2, No. 11), via Gallica

Le Bulletin du Norddeutscher Lloyd de Bremen, Nov. 1907 (Vol. 2, No. 11), via Gallica

Barroin’s creations were shown alongside those of Worth and Pingat, among others. This late 1890s red velvet gown, then, coincides with a time in which P. Barroin was cementing its position as a preeminent Parisian couture house. A fashion columnist for Figaro in 1907 notes that Barroin’s clothing was worn in all the fashionable spaces of Paris: “[Barroin’s] dresses have so much success at the races, the theater, and in the city.”[5] Newspapers frequently mention that Barroin catered not only to the Parisian aristocracy, but also to foreigners and the wives of colonial officials, who could place orders by traveling to Paris. One Tunisian newspaper (Tunisia was a French protectorate from 1881-1956) describes how a department store buyer returned from Paris with the latest fashionable clothing from “Barroin, Callot soeurs, and Paquin” that would then be available for purchase in Tunisian expos or stores.[6] Barroin’s international appeal makes it likely that this red gown was part of several outfits ordered by a wealthy woman, probably an American woman, who found herself in an elite resort town in Southern California. Oftentimes, these clients would purchase their wardrobe in Paris or they would have their dressmaker in Paris make customized dress forms for them so that they could order from the United States.[7]

Through observation and research, a seemingly simple red gown can demonstrate the sensory power of fashion as well as new insights into little-known dressmakers from the turn of the century, the geo-economic landscape of 19th century French haute couture, and American Gilded Age purchasing practices. A big thank you to Christina Johnson, Kevin Jones, Carolyn Jamerson, and Joanna Abijaoude for their assistance with this project!

Kasia Stempniak (far right) with FIDM Museum Curators Christina Johnson and Kevin Jones

Kasia Stempniak (far right) with FIDM Museum Curators Christina Johnson and Kevin Jones

[1] Dorothy Parker, “The Red Dress” in American Poetry: Henry Adams to Dorothy Parker, ed. Robert Hass. (Library of America, 2000), 879.

[2] Ingrid Mida and Alexandra Kim, The Dress Detective: A Practical Guide to Object-Based Research in Fashion (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), 29.

[3] The dressmaker “C. Barroin” is listed in the Paris directory as early as 1862 at the address 10 rue Favart. It is possible that this may have been Paul Barroin’s father or family member who set up the store in the mid-19th century.

[3] Ibid, 62.

[4]See Figaro. No. 308. 4 November 1906. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k287528h.item

[5] My translation. Ghenya. “La Mode aux courses.” Figaro. No. 112. 22 April 1907. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k2876987.item

[6] La Dépêche tunisienne. 21 October 1900. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k580088q.item

[7] Coleman, Elizabeth Ann, “Acquiring a French Wardrobe” in With Grace and Favour: Victorian and Edwardian Fashion in America, ed. Otto Theime, Elizabeth Ann Coleman, Michelle Oberly, and Patricia Cunningham (Cincinnati: Cincinnati Art Museum, 1993), 2.