Confessions of a Curator: Fashioning Fido

We're back with another edition of Confessions of a Curator, blog entries written by our Curators about their ongoing projects and special interests. Dog lovers, it's your lucky day: Associate Curator Christina Johnson treats us to a history of dogs in fashion, spurred by the gift of an adorable 1903 puppy fan from our generous donor Mona Lee Nesseth. Enjoy!

****************************************************************************************************************

Fan, 1903

Fan, 1903

Maison Duvelleroy

Adolphe Thomasse, artist

Gift of Mona Lee Nesseth, 2016.975.12

Anyone who really knows me knows I love dogs. I always have—ever since I was a child. Growing up, our dogs were treated as beloved family members and I was deeply attached to them. Today, I spoil my own dogs and admit to watching more than my fair share of funny dog videos online. More seriously, I consider my activities in canine rescue and advocacy some of the most important accomplishments of my life.

Les Modes Parisiennes Peterson’s Magazine

Les Modes Parisiennes Peterson’s Magazine

July 1869

2015.897.86

Gift of Steven Porterfield

Ok, so maybe you’re asking, “Great Christina, you’re obsessed with dogs! What does this even have to do with fashion?” Well, it turns out people have long been obsessed with their canine companions—just as much as fashion. Dogs have made their way into fashion plates, portraits, jewelry, fans—you name the fashionable accessory and I can show you a dog.

Portrait of Archduchess Maria Christina, Duchess of Teschen

Johan Zoffany, 1776

Courtesy Kunsthistorisches Museum

A bit of history: scholars believe dogs were domesticated thousands of years ago. Wild dogs developed connections to people who fed them scraps of food in exchange for their guarding and herding abilities. Emotional attachments most certainly formed. Let’s fast forward to the Early Modern era (about 1500-1800): diminutive “lap” or “toy” dogs were considered an intrinsic part of the domestic, feminine sphere—at least for wealthy ladies. Small dogs often make their appearance in period portraiture, generally on their mistress’s lap. Popular breeds were artistically recorded as an intrinsic part of a privileged setting, one item in a litany of important accessories required by those in Society, which also included the latest luxurious furnishings and fashions.

Brooch with ambrotype of dog & lock of fur

1860-1880

Gift of Andrea Tice in memory of Carmelita Johnson

2008.46.81

Designer dog breeds are nothing new; they were all the rage in the mid-nineteenth century. Victorians’ interest in Darwinian classification and evolution coupled with commercial desires for what social theorist Thorstein Veblen (1857-1929) later termed “conspicuous consumption” causing pups to be selectively bred and valued unlike ever before. The first recorded dog show in Great Britain was held in 1859.[1] Our own American Kennel Club was founded in 1884. That year, one author expounded: “The best products of the kennels of Europe and quaint sorts from the far East are eagerly sought for by our people, without regard to cost.”[2] There was also a growing concern for animal welfare during the late-nineteenth century; shelters were opened for lost dogs, the veterinary profession was established, and pet cemeteries appeared.[3]

So what about that charming brisé fan posted at the beginning of the blog? When our amazing FIDM Museum benefactor and Fashion Council member Mona Lee Nesseth showed it to Kevin and me recently, we knew we had to acquire it. Mona has been instrumental in underwriting the purchase of many astounding fans for the FIDM Museum over the past few years, and this one is now officially my favorite. It’s signed “Duvelleroy Paris” and is quite small at about six inches high by six inches across. It depicts the front and back of a spaniel’s head—life size mind you. Specifically, this is a “Blenheim” King Charles Spaniel (a breed related to today’s Cavalier King Charles Spaniel). The breed descended from the chestnut and white hunting spaniels kept by the first Duke of Marlborough (1650-1722) at Blenheim Palace, his estate in Oxfordshire, England. A riding whip is rendered on the guard, referencing the fact that these spaniels were specifically bred to join the hunt, rushing at underbrush or wading into water in order to search out birds. Our little pup (let’s call him Fido) wears a studded collar and his silky coat is well-groomed, suggesting he represents a domesticated pet who “belonged” to someone.

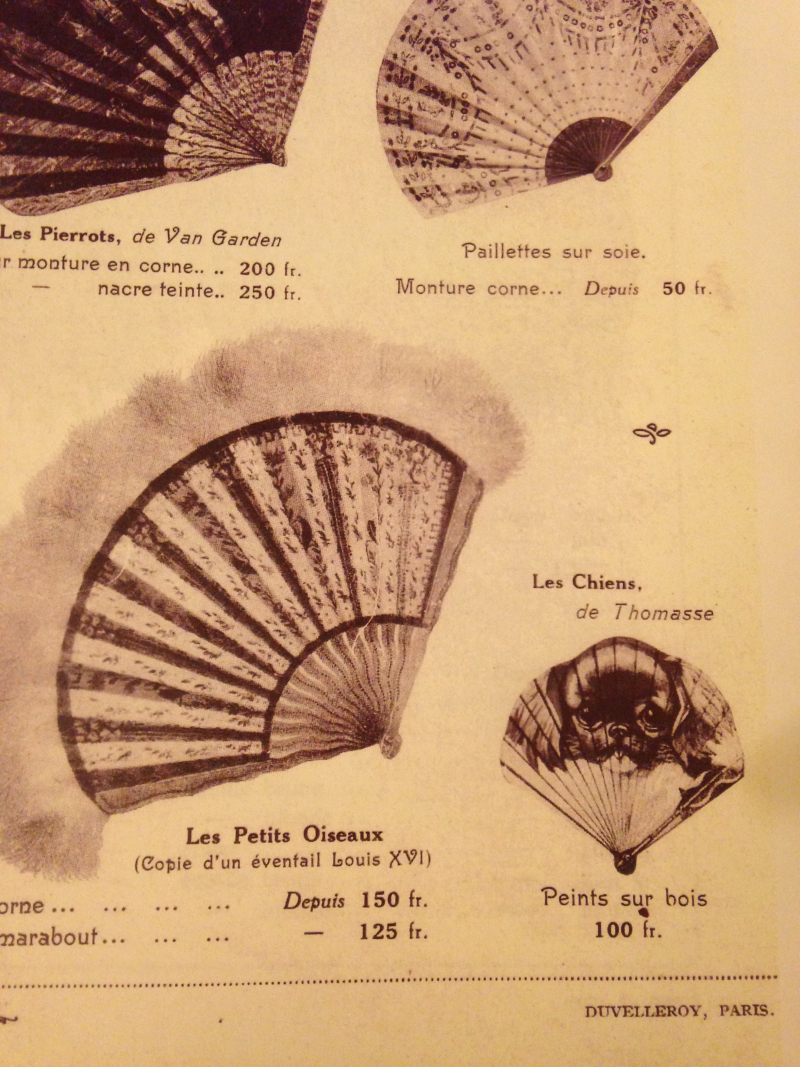

Duvelleroy Paris catalog, 1903, page 6.

Duvelleroy Paris catalog, 1903, page 6.

Fido’s diminutive size made me wonder if this could be a child’s fan, but it’s extremely delicate. A tyke would easily snap apart the wafer-thin wooden sticks and scratch the finely rendered, unvarnished paint. I searched French sources for contemporary references to this treasure and found it advertised in a 1903 Duvelleroy catalog. Fido shares the page with a group of more traditional feathered and sequined fans—all women’s. Nowhere is the little spaniel fan described as a child’s. Then it dawned on me, the size is about the same as fans of a century before—it’s simply Empire Revival size; the small scale makes it all the more precious. Note size does equate to cost. The much larger spangled fan above it is only 50 francs, while the more substantial feather fan nearby is only 25 to 50 francs more than our painted wood chien de Thomasse, priced at 100 francs.

This sweet little pup is just one of the famous animal fans painted by Adolphe Thomasse (1850-1930), often sold by Duvelleroy (company active 1827 to present). Thomasse painted a menagerie of lifelike animals, including dogs, cats, and birds. The FIDM Museum’s King Charles Spaniel fan was the perfect accessory for a turn-of-the-century dog fancier who may have read about the Blenheim spaniels in a 1901 guide to show dogs: “Much has been said about these dogs being inclined to be ill-tempered, but it is certainly a gross libel, as they, like the rest of the small spaniels used in the field, are most gentle in disposition.”[4]

Do you really think I would end my blog post without bringing it back to my own obsession? Since you asked, I just happen to have a photo of one of my own cherished dogs to show you. Don’t you think Clementine would look great as a hand-painted fan? I know I’d buy one!

[1] Vesey-Fitzgerald, Brian. The Domestic Dog. London: Routledge, 1957. 143

[2] The Century, May 1885. Re-published in Derr, Mark. A Dog’s History of America. New York: North Point Press, 2004.

[3] Howell, Philip. “A Place for the Animal Dead,” in At Home and Astray: The Domestic Dog in Victorian Britain. Charlottesville and London: University of Virginia Press, 2015.

[4] Huntington, Harry. The show dog; being a book devoted to describing the cardinal virtues and objectionable features of all breeds of dogs from the show ring standpoint…” Providence, RI: Remington Print Co, 1901. p192