A Colony of Colors: The Iconic Playboy Bunny

Hugh Hefner passed away on September 27 at the age of 91. Although a highly controversial figure, he made lasting contributions to American pop culture (and Los Angeles in particular). Below, Curator Kevin Jones shares his research on the iconic Playboy Bunny uniform, donated to the Museum in 2013 by Melissa Mandolf-Smith.

****************************************************************************************************

The adult entertainment magazine Playboy is as ‘American as apple pie,’ as the cliché goes. Hugh Hefner, a former copywriter for Esquire magazine, had an idea to start a men’s magazine which not only tapped into the male sexual zeitgeist, but at the same time educated him about music, literature, and sports. The first issue of Playboy debuted in December 1953. As for the ubiquitous Playboy Rabbit logo, Hefner explained: “I selected a rabbit as the symbol for the magazine because of the humorous sexual connotation, and because he offered an image that was frisky and playful. I put him in a tuxedo to add the idea of sophistication…[which] struck me as charming, amusing and right.”

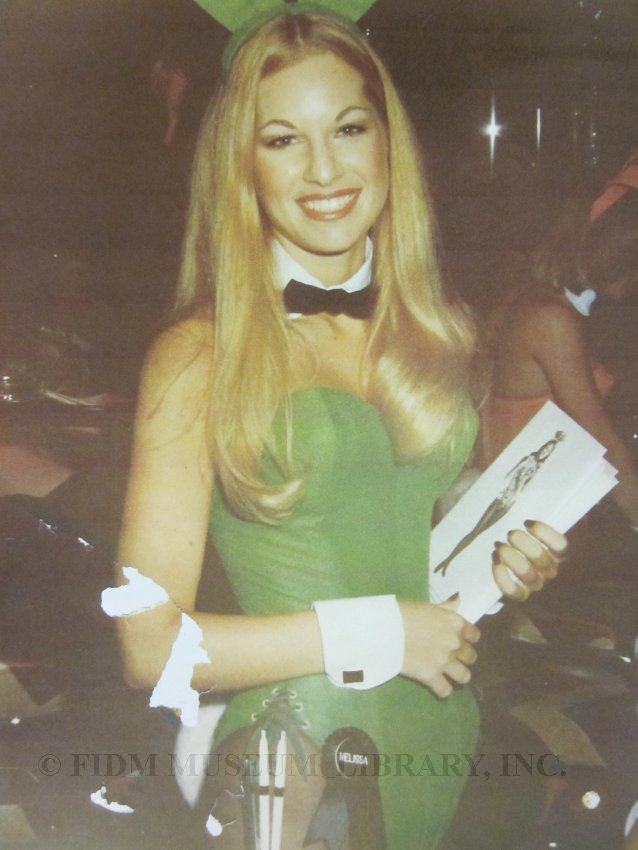

Playboy Bunny Uniform, c. 1977 Gift of Melissa Smith 2013.1231.1A-P

The Mondrian-inspired Chicago Playboy Club opened in 1960, and this next phase in the development of the Playboy mystique became an immediate success. Clubs opened far and wide, from Los Angeles to New York to London to Tokyo. In 1959, Victor Lownes, Promotions Director, was dating playmate Ilsa Taurins, who suggested using the tuxedo-clad Rabbit mascot as the inspiration for the Chicago Club’s waitress costume. Lownes later reminisced: “It was my girlfriend’s concept. The bunny was originally intended as a male symbol…the playboy of the animal kingdom. When Hefner decided to open the clubs…he finally came around to our idea to make the bunny into a female.” And, conveniently, Ilsa’s mother was a seamstress who stitched up the prototype.

First modeled by Cynthia Maddox, Hefner’s then girlfriend—with ears and tail, but no collar or cuffs—the outfit was underwhelming. Hefner wanted two things changed: 1) cross-lacing added to the hips and 2) the sides of the garment tucked up and under, revealing more of the upper thigh than swimsuits of the day. The one-piece rayon satin garment was originally mounted on a merry widow corselet; its hourglass foundation was more reminiscent of the post-World War II “New Look” than early 1960s shift styles, but Hefner was conjuring past ideals.

Despite these firsthand accounts about the development of the outfit, New York designer Zelda Wynn Valdes has been given credit for the creation of the Bunny costume. How she supposedly became connected with Hugh Hefner in Chicago is unknown, and the only reference I could find of this partnership is noted in her 2001 New York Times obituary. Perhaps Valdes’s company sewed the costumes for the New York Club, and this conceivable involvement was later comingled with her design career, thus giving her undue credit for the original idea. By 1961, the well-known collar, bow tie, and cuffs were in place, along with a rosette nametag pinned to the hipbone. The ears and shoes always matched the color of the body of the suit. Mesh tights were initially worn, but they were replaced in 1962 with sheer black Danskin stockings worn over flesh-tone tights. And finally, in 1969, the stuffed, faux-fur tail replaced the original yarn tail. The look was complete.

In 1977, 24-year-old criminology student Melissa Mandolf—donor of the Bunny costume in the Museum’s Collection—tried out for a position in the new Dallas Club in Texas. Out of about 2,000 applicants selected for an interview, Melissa was chosen as one of the 189 finalists to parade down a runway in high heels to disco music before a panel of celebrity judges. Much to her surprise, Melissa “won her ears,” securing one of the coveted 80 Bunny positions. Aside from the prestige of being counted among the Bunny ranks, money was the biggest draw: Melissa knew the position could help her pay for college. She recalls: “Many thought it was a glamorous job, but it was VERY hard work. And I remember being so miserable with those shoes. My feet ached all the time.”

Each new Bunny was supplied with two costumes, which included the ears, tail, collar and cuffs, and every outfit was custom made. A full-time seamstress was on hand for “stuffing, jerking, pulling, and cramming” the Bunnies in. And when it came to the Bunnies’ most obvious assets, Angelyn Chester of the Chicago Club confessed: “Oh, everybody stuffed. I had an hourglass figure…but you had to stuff the cups to give lift. There was actually a pocket in the cup where you could insert whatever you needed to.” The Bunny costumes were to be turned in to the wardrobe mistress at the end of each shift for laundering and mending. Not one piece of the outfit was allowed out of the building; Melissa noted that the “only items we were allowed to take home each night were our cuffs and collars…as we were responsible for keeping them cleaned and starched…” Because of the bodice’s interior construction, it was not easy to bend forward, which could result in popped seams or force metal bones through the satin covering.There were choreographed moves that needed practicing before attempting to balance a tray of drinks or light a cigarette; the most famous was the ‘Bunny Dip,’ developed to serve drinks at a table.

There was a colony of colors at each Playboy Club—surprisingly, colors were bestowed to Bunnies by lottery! Melissa explains: “We all drew numbers and if you were number one you got to select whichever color you wanted and it went from there….The color black was the most popular and went first.” In some clubs, black was reserved for the most experienced Bunnies. There were also specialty colors and fabrics for various parts of the clubs or seasons of the year. In all the VIP Rooms, Bunnies wore blue velvet. At Christmas, ‘Door Bunnies’ donned red suits with white fur trim, and on St. Patrick’s Day in Boston they wore green ears and tails. Some costumes were earned: Bunnies voted ‘Bunny of the Year’ at individual clubs wore a silver lamé costume. These Bunnies went on to compete in a pageant to become ‘International Bunny of the Year’—the winner elevated her commodity status to gold lamé. Polychrome Bunny costumes became an option at the 1966 opening of the London Club. Patterned costumes even appeared on the high seas in Playboy’s floating Atlantis Club.

Donor Melissa Mandolf-Smith wearing her Bunny uniform, c. 1977

Donor Melissa Mandolf-Smith wearing her Bunny uniform, c. 1977

What did our Bunny Melissa think of her costume? “I HATED green and it was the ONLY color I would never wear, and have never had in my closet!!” Unfortunately, the rainbow was depleted by the time her lottery number was called and only green was left. Her suffering was short lived, though, as she stayed at the Dallas Club for just four months, but used her Bunny training well by flying with Southwest Airlines as a flight attendant for thirty, happy years.